Inspecting the Aftermath: Residents of Buffalo creek worried constantly about the stability of the slurry dams upstream. Nothing was done. Photo courtesy of West Virginia State Archives.

I woke up this morning to a frozen world. Fog and ice descended on the hills above Boone, N.C., last night and are still waiting around for the thaw. It was silent other than the periodic crack of a branch and the following echo that bounced around the hills. Stepping outside after reading Ken Ward Jr.’s remembrance of the Buffalo Creek Flood, I wondered if this stillness was similar to what the residents of communities in Logan County, W.Va., felt that morning 41 years ago today.

To contain the refuse of a coal preparation plant operated by Buffalo Mining Co., a series of three dams were built upstream from the communities along Buffalo Creek in the 1950s and 60s, as Logan County continued to grow into one of southern West Virginia’s prolific coal-producing counties. Dam No. 3, the largest, stood 60 feet above the pond and downstream dams below. When it gave way on the cold morning of Feb. 26, 1972, the others collapsed instantly.

The poor construction and regulation of coal waste impoundments that precipitated the Buffalo Creek Flood intensified during boom times when coal preparation plants used more water and produced more slurry just to keep up with coal production. As Jack Spadaro, a former superintendent at MSHA’s Mine Health and Safety Academy, told me for a story last year, “All along, as these dams were being built, they weren’t really constructed using any engineering methods. They were simply dumped, filled across the valley.”

Rushing through Buffalo Creek hollow, the slurry carried with it semi-rotten trees, rocks and sediment. It ripped homes from their foundations and swept up cars and bridges until it finished three hours and 15 miles later at the Guyandotte River, destroying nearly everything in its path. When the physical chaos settled, out of a population of around 5,000 people, 125 were killed, 1,121 injured, and more than 4,000 were left homeless.

Looking back, it may seem like a black swan event, an outlier unpredictable in scope or consequence. But Spadaro and others did not see it that way. For too long, companies had constructed impoundments with little regard for communities downstream. Laws were passed requiring the creation of a nationwide inventory of dams, and better inspection and enforcement. In the years after Buffalo Creek, improved oversight likely saved hundreds if not thousands of lives.

Recently, victories have been achieved by those unwilling to live with the threat of coal slurry, whether it is underground or hidden among the hilltops. In January of this year, the nearly 200 students of Marsh Fork Elementary ran excitedly for the first time through the halls of their new school. For years, the students and faculty of Marsh Fork worked, studied and played in the shadow of a coal silo and 400 feet downslope from an impoundment owned by Massey Energy that held back billions of gallons of coal slurry.

After five years of protests, arrests and nationwide publicity, students of Marsh Fork Elementary began the year at a new school. Photo by Vivian Stockman.

Another success came in 2009, when the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection adopted a self-imposed moratorium on new permits for the underground injection of slurry. Class action lawsuits dating back to the early 2000s over community-wide contamination from slurry have led to expanded municipal water lines and settlements taken by coal companies to avoid trial have reached $35 million.

But unlike Spadaro, and others I spoke with last year around the 40th anniversary of the flood, many respond to black swan events with the hard-to-resist rationalization that comes naturally with hindsight. Maybe that rationalization would be fine, had the underground honeycombs of abandoned mines held back the one billion gallons that inundated Martin County, Ky., in the October 2000 spill reminiscent of Buffalo Creek disaster. It may have been fine if recommendations of a 150-foot barrier were not routinely ignored as onerous and unnecessary before the mere 15 feet of rock containing the slurry collapsed like a trap door and coated nearby creeks and communities with a substance whose texture can only be described as “sludge.”

Buffalo Creek and Martin County were called “acts of God,” by those most unwilling to ask hard questions, look for answers or accept blame. It’s a rationalization of the highest order that distracts from the causes of disasters that have more appropriately been called “acts of man.”

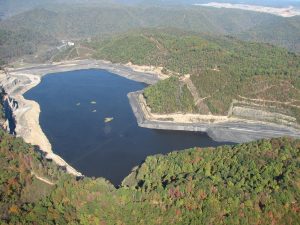

When the Brushy Fork impoundment reaches its permitted capacity, 9 billion gallons of slurry will be held in the 645-acre reservoir. Photo courtesy of Vivian Stockman

The coal industry may leave Appalachia, but Appalachia will never be able to leave the coal industry. Mountaintop removal mines and carved-out basins that hold billions of gallons of toxic coal waste are scars that last. Arguments used to rationalize these practices have sunk in, but usually don’t stand up to scrutiny. I was sad but unsurprised, for example, to find out that creating liquid slurry is only marginally cheaper — for coal companies at least — than using a dry-filter press which uses less water and creates less waste.

Faced with any criticism, the coal industry has its frequent incantation that “coal keeps the lights on” to fall back on. Remember to ask: “But at what cost?” Borderline monopolistic utilities like Duke Energy that continue to support mountaintop removal with their purchasing power will keep telling us not to worry about what goes on behind the light switch. Tell them “too late.”

Mat Louis-Rosenberg of the Sludge Safety Project speaks to the media and public in the West Virginia State Capitol rotunda. Photo by Vivian Stockman.

The harder it is for negligent coal companies to relinquish the responsibility for the waste they create, the harder it will be to rationalize something as shortsighted or enduringly harmful as the Brushy Fork impoundment, a 645-acre reservoir behind a 900 foot dam with a permitted capacity of nine billion gallons that looms over towns in Raleigh County, W.Va.

I’m thankful for the work of those who have taught me about the problem of slurry, including Rob Goodwin and Mat Louis-Rosenberg, watchdogs and organizers for Coal River Mountain Watch’s Sludge Safety Project, and Dr. Ben Stout from Wheeling Jesuit University who tested the water in Mingo County, where the indiscriminate injection of slurry contaminated well water. As much as the industry has tried to hide this dirty secret, there will always be those that are unwilling to accept a rationalization handed down from those who profit from it. For there is none.

“There is no truly good solution to a poisoned aquifer,” Mat-Louis Rosenberg put it to me last summer, “that’s a resources that’s been taken away from people forever that can never be fixed. There’s no true justice for something like that.”

Leave a Reply