However complex the causes of the ongoing health crisis in Appalachia, denial accomplishes nothing but the perpetuation of the status quo. Yet every time claims that could negatively impact the coal industry surface, Appalachian legislators throw up a black sheet.

West Virginia University professor and public health researcher Dr. Michael Hendryx’s latest article, “Personal and Family Health in Rural Areas of Kentucky With and Without Mountaintop Coal Mining,” appeared in the online Journal of Rural Health a couple of days ago. The study immediately gained the attention of Kentucky media, and supporters of the coal industry have been quick to write off Hendryx’s methods and conclusions — they just haven’t gotten around to reading it yet.

Hendryx has published more than 100 peer-reviewed articles. He’s the director of the West Virginia Rural Health Research Center and after receiving a Ph.D. in psychology, he completed a post-doctoral fellowship in Methodology at the University of Chicago. Little of that seems to matter, however, because much of his research is concentrated on poor health in Appalachian coal-mining communities, especially those where mountaintop removal takes place.

Like other studies Hendryx has conducted, the eastern Kentucky-focused article relies on comparing data gathered in counties with mountaintop removal to data from counties without it. More than 900 residents of Rowan and Elliott counties (no mountaintop removal) and Floyd County (mountaintop removal) were asked similar questions about their family health history and incidents of cancer to those that the U.S. Center for Disease Control uses in gathering data.

After ruling out factors including tobacco use, income, education and obesity, the study found that residents of Floyd County suffer a 54 percent higher rate of death from cancer, and dramatically higher incidences of pulmonary and respiratory diseases over the past five years than residents of Elliott and Rowan counties.

These results should surprise no one, least of all the families in Floyd County that participated in the study. Yet somehow, supporters of the widespread use of mountaintop removal still refuse to consider that blowing up mountains might impact human health.

Over the years, Hendryx has repeatedly cited air pollution near blasting zones as a culprit. Due to the destructive nature of mountaintop removal, exposure to coal-related pollution is significantly higher in communities near these mines than in those where traditional underground mining occurs. Sounds reasonable enough, right?

“I don’t believe that stuff for a minute,” Kentucky Speaker of the House of Delegates Greg Stumbo is reported as saying in Ashland, Ky., newspaper The Independent. “I’ve lived there all my life. There are no pollutants in the air. When you blow up something, it’s just dust for a little while and that’s the end of it. It’s not like the sky is blackened every day.”

We’re led to believe that, “I don’t believe that stuff for a minute,” is the entirety of Stumbo’s position on the research incriminating mountaintop removal.

The president of the Kentucky Coal Association, Bill Bissett, also remains skeptical of Hendryx’s methods and motivations. He’s quoted in The Independent as calling Hendryx “a researcher who begins his research with a bias against coal and its extraction.”

It’s not the first time Bissett, speaking officially from his own biases, has been the messenger to refute Hendryx’s conclusions. Last year, he called Hendryx “an anti-coal ideologue masquerading as an ‘objective researcher.’” His argument is essentially that, because the studies have been widely publicized and gained favor with environmental and public health advocates alike, Hendryx must have been put up to it.

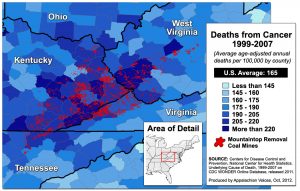

A 2012 Appalachian Voices' report mapped the findings of peer-reviewed health studies and data from the U.S. Center for Disease Control, United Health Foundation and the Gallup-Healthways Well-being index.

Sure, groups including Appalachian Voices, the Sierra Club and Kentuckians for the Commonwealth have cited Hendryx’s studies in indictments of mountaintop removal. But unlike Bissett, whose salary depends on echoing the position of unscrupulous coal companies no matter the cost, Hendryx does not receive funding from environmental groups that would unlikely be interested in influencing the outcome of his research anyway.

Stumbo and Bissett may be avoiding a thorough review of the case against mountaintop removal to prevent their conscience from getting in the way. So instead, they and far too many others are content to blame the unhealthy lifestyles of some living in eastern Kentucky and southern West Virginia while evidence to the contrary grows.

Hendryx, like any ethical researcher would, acknowledges that even after ruling out other health factors his studies reveal correlations and are too limited to pinpoint the exact chemical or cause of the disproportionate cancer rates in communities with the most mountaintop removal. But after conducting dozens of studies based on thousands of interviews, his research reveals patterns of correlations — the prevalence of cancers and other ills increases with the amount of mining.

What is needed to determine a direct cause, Hendryx told the Louisville, Ky., Courier-Journal, is a “gold standard” study that would measure air and water quality in and around people’s homes, and analyze blood and hair samples to reveal exposure to pollutants — another reasonable recommendation from this so-called anti-coal ideologue. No such “gold standard” study has been conducted.

So the burden of proof unacceptably remains on those who suffer the greatest impacts. Any ground made in slowing the destruction of the Appalachian Mountains has been made by the people speaking out, and time has shown that those who’ve watched their air and water poisoned and their family’s health decline often have the loudest voices.

As for politicians and coal executives operating in Appalachia, ranks are rarely broken. It is telling that Patriot CEO Ben Hatfield’s deflated admission last year as the company was forced to begin phasing out mountaintop removal that “Patriot Coal recognizes that our mining operations impact the communities in which we operate in significant ways,” was so widely cheered it was practically accepted as a guilty plea.

There is little doubt that subsequent studies will continue to cite the pervasive and irreversible environmental impacts of mountaintop removal as harmful to human health. But rather than taking action or supporting additional study, Appalachian legislators have questioned the credibility of the research and individuals and seem satisfied to deny the conclusions out of hand, if they get around to reading them.

However complex the causes of the ongoing health crisis in Appalachia, denial accomplishes nothing but the perpetuation of the status quo. Yet every time claims that could negatively impact the coal industry surface, Appalachian legislators throw up a black sheet.

In the study’s conclusion, and based on his findings, Hendryx writes:

“The national goal to eliminate Appalachian health disparities will not be achieved unless disparities are eliminated in [mountaintop mining] areas, and that means not simply ending mountaintop removal, but creating better economic opportunities and environmental conditions in these disadvantaged communities.”

Scientists, academics, activists and citizens are asking the hard questions, and they have been for some time. But it has not yet been enough to dismantle the denial of people like Speaker Stumbo or Bill Bissett.

Leave a Reply