AV's Intern Team | December 19, 2014 | No Comments

By Megan Northcote

Robert Morgan crafts evocative sculptures from found materials. “Pangean Youth,” completed in 2011, stands 42 inches tall.

An Avatar-blue, 42-inch doll with spiked, glitter-plastered hair stands erect amidst a colorful pile of trinkets. One outstretched arm defiantly wields a miniature sword as a snake coils tightly around the doll’s torso, its open mouth poised to attack.

So stands the “Pangean Youth,” a found-art sculpture commemorating Lexington, Ky. artist Robert Morgan’s troubled friend whose naked, blue-tinted body was found lying in a parking lot after a heroin overdose years ago.

Morgan helped save his friend’s life that night, which, years later, helped save his own.

Growing up in an impoverished part of eastern Kentucky, Morgan would spend hours “collecting little things” from trash piles and creating “something out of nothing” with the guidance of his mom, a self-taught artist.

After years of battling drug and alcohol addictions, Morgan, now sober and in his sixties, has returned to his childhood passion of collecting found objects to create art that tells humans’ stories. “I’m always looking for ways to package peoples’ stories that no one wants to hear,” he says. His pieces have reflected the historic Lexington cholera outbreak, the 1980s AIDS epidemic, addictions and suicides.

Morgan’s work blends the unusual — electronic parts, rusty springs, doll heads and gaudy carnival prizes — with special finds, such as discarded knickknacks.

No solid boundaries define the work of contemporary Appalachian artists like Morgan. Some artists are regional natives, others recent transplants. Some pull from the narratives and imagery embedded in the region’s landscape and culture, while others reject tradition and embrace globalized, innovative approaches to their work. Yet what unites all of these artists are the stories they each hold, waiting to be told.

Recycled art using found objects is an emerging trend in Appalachia and across the globe.

Mary Saylor, a 3-D mixed media artist and East Tennessee native, moved back to Knoxville three years ago. Working in an animal clinic inspired her to create papier-mache animal sculptures using primarily recycled materials, such as brown paper bags and toilet paper tubes, as well as found vintage objects.

“I’m big into recycling and wanted to reduce my carbon footprint through the work that I do,” says Saylor.

Making greener art can also happen in the literal sense — using found objects from nature.

Lowell Hayes, a native Tennessean now residing in Valle Crucis, N.C., has focused the latter half of his career on landscape art, specifically 3-D bas-relief construction paintings of Appalachia, using only natural materials gathered from his wooded backyard.

“People tell me that it feels like you can walk right into my work and that’s exactly what I work to achieve,” says Hayes, a retired art instructor from Appalachian State University.

Like many artists, moving back to Appalachia after an extended absence made him more fully appreciate the beauty of the mountains and advocate for them through his art. For example, one of his more recent series featured the Carolina Hemlock trees and helped raise awareness for this native species threatened by the woolly adelgid.

Exhibiting a representative sample of Appalachian artists living and working across the region is no small feat. Yet every other year, the William King Museum in Abingdon, Va., showcases a juried exhibition, From These Hills: Contemporary Art in the Southern Appalachian Highlands, which does just that.

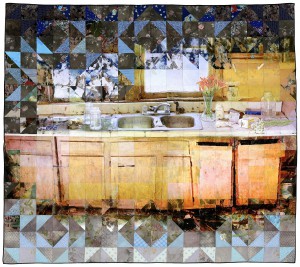

Jeana Eve Klein’s Abandoned House Quilts combine the reality of the present with imaginings of the past. The North Carolina artist’s 2012 work “Any Day in June” is comprised of acrylic paint, digital printing and dye on recycled fabric and is 63 inches tall by 69 inches wide.

The 2013 show included mixed media Abandoned House Quilts from Jeana Eve Klein, associate professor of fiber arts at Appalachian State University. Her pieces transform regional quilting traditions through a playful process that explores the forgotten human stories behind these houses; each quilt splices together manipulated digital images of self-discovered abandoned houses, which were then superimposed onto fabrics, sewn together and embellished with paint.

Likewise, Simone Paterson, associate professor of new media art at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, whose work was also showcased at the 2013 show, explores digital media art. Through her installations, she juxtaposes traditional craft, particularly sewing and textile arts, with computer technologies, including video projection and photography.

As an Australian native, Paterson’s recent exhibition, “The Nest,” commemorates her earning American citizenship. The installation is designed to provide audiences with an outsider’s aerial view of America, featuring large mural landscape prints and three woven nests, each containing projected images of dogs, cats and Paterson herself, narrated by the sounds of nature’s rhythmic breathing.

For 24 years, Blue Spiral 1, a prominent art gallery in Asheville, N.C., has showcased a sampling of regional artists’ work.

“The things that interest me and my gallery the most are those works that stem from traditions, but are a more modern take on those art forms,” says Jordan Ahlers, gallery director.

One of these artists is Michael Sherrill. Since moving to western North Carolina in 1974, Sherrill has blurred the lines between traditional mediums, creating a hybridization of clay, glass and metal in his 3-D sculptures.

Having cultivated his craft for years under Penland School of Crafts’ internationally recognized instructors, Sherrill feels compelled to support the region’s next generation of artisans.

He currently serves as board president for the Center for Craft, Creativity, and Design in Asheville, which annually awards the prestigious Windgate Fellowship to 15 collegiate art students nationwide.

A detail from Charles Jupiter Hamilton’s Westside Wonder Mural in Charleston, W.Va., depicts community faces. Photo by Bob Lynn.

“The creativity we have here [in Asheville and the Appalachian region] is our greatest commodity,” Sherrill says.

Photographer Megan King graduated from East Tennessee State University in 2013 with degrees in Spanish and photography. A native of Bristol, Tenn., her photography series, “Hispanic Appalachia,” was selected for the 2013 From These Hills exhibition.

Growing up in a more conservative Appalachian community, King wanted her images to raise awareness of the rapidly growing Hispanic populations in East Tennessee in the hopes of building acceptance and easing racial tensions.

Contemporary art in eastern Kentucky is often centered around the folk art of self-taught artists, says Matt Collinsworth, director of the Kentucky Folk Art Center in Morehead.

“The hotbeds of self-taught artists tend to be found in economically depressed areas,” says Collinsworth. “Even though it’s stylistically primitive, folk art is very much contemporary art.”

John Haywood is one of these self-taught artists. A native of Risner, Ky., Haywood has turned to his work as a tattoo artist to reconnect with and commemorate his Appalachian roots, which he once shunned.

At 13 years old, Haywood allowed his friend’s untrained older brother to give him his first tattoo — a Misfits skull from the popular American punk-rock band. From that point forward, he was hooked.

By the summer of 2004, he worked in Radcliff, Ky., tattooing soldiers on leave from Fort Knox. After five years of filling non-stop tattoo requests, Haywood returned to Whitesburg and opened his own shop, The Parlor Room, in 2011.

Haywood esteems tattooing as a fine art, incorporating the painting principles he learned earning a master’s degree at the University of Louisville. Yet, he says he is most proud of those tattoos he creates that reflect a regional identity and confront Appalachian stereotypes. “Here [in Appalachia] I get to do tattoos that come from the minds of people who have a similar background as me. I don’t want my art to go over people’s heads.”

Charleston, W.Va.

Morgantown, W.Va.

Knoxville, Tenn.

Wise, Va.

Boone, N.C.

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests