AV's Intern Team | February 18, 2015 | No Comments

By Matt Grimley

Warren Wilson College field school students help uncover Appalachia’s 16th-century Spanish history at the Fort San Juan excavation site near Morganton, N.C., in June 2014. Here, the students are sifting for artifacts. Photo courtesy Warren Wilson Archaeology Lab

A small clay bead. A hunk of carved soapstone. A shattered pipe.

“You can’t put a shovel in the ground at the Berry Site without finding artifacts,” says David Moore, an archaeology professor at Warren Wilson College outside of Asheville, N.C.

Before Sir Walter Raleigh or the Puritans, there were the Spanish. Since nearly the start of the 1500s, they had marched through swamps and forests into the heart of the yet-to-be United States. They were fresh from conquests of native populations in Central and South America, and they wanted more. More state-level societies to manipulate for their economic gain. More silver. More gold.

In 1566, Juan Pardo and his troops built six forts as they plowed from the Carolina coast to the Appalachians. Historians knew the locations of these forts from Spanish documents, but no supporting archaeological evidence had ever been found.

That is, until a couple years back. The Berry Site, located on a tributary of the Catawba River near Morganton, N.C., was home to the Native American town of Joara, as well as Fort San Juan, which the Spanish built in 1567. After digging for years, Moore’s group finally uncovered a ditch outlining the fort, giving life to what they had only read of.

Now they had to show it to the world and keep it safe.

“Preservation in archaeology is a tricky subject,” says Moore. “For us, preservation involves as much education as anything else.”

Above the south end of the old Fort San Juan moat, Warren Wilson College students help excavate the site near Morganton, N.C. Photo courtesy Warren Wilson Archaeology Lab

Moore’s archaeological team is composed of students and fellow academics. They work mainly with private landowners who are willing to preserve their sites and allow access to researchers.

History, it seems, is lost every day: already, Christmas tree nurseries and other landscaping projects have ruined about 25 potential research sites in the area. Moore notes that Exploring Joara, an educational archaeology nonprofit that he helped to create, brings in school groups and kids to their dig sites. The group’s interpretive center has also helped educate local governments, businesses and people, totaling more than 10,000 contacts just last year. He hopes that Joara will encourage local residents to think back on the land and its layered history, and to help conserve it.

After building their fort, the Spanish lasted only 18 months in the Appalachians. The native people, realizing their gifts of food and services would not be reciprocated, burned down the strange forts and killed all but one soldier. The Spanish failure opened the way for the English and the dramatic morphing of the American frontier.

The Sense for Change

At the center of preserving history is the growing market of heritage tourism, where travelers schedule their vacations around historical landmarks. It’s a booming industry, according to a 2009 study from the U.S. Cultural and Heritage Tourism Marketing Council, with more than 110 million heritage-driven tourists pumping $192 billion into the U.S. economy every year.

Many communities find that investment into landmarks yields more money. The Appalachian Regional Commission reported in 2010 that every 40 cents the federal agency spent on tourism projects spurred another dollar in private investment. In the case of Burke County, N.C., for example, where Joara and Morganton are located, tourism jobs increased 5.8 percent in 2013 alone. That’s the largest jump in such jobs out of any North Carolina county that year, says Ed Phillips, director of the Burke County Tourism Development Authority.

History abounds underfoot, and yet material preservation is often facilitated only by a single mean: ownership.

“To control your own destiny,” says Rick Wood, Tennessee state director of the Trust for Public Land, “you have to buy a piece of property.” Landowners, he says, can also protect the land in perpetuity through an easement, a legal arrangement where an organization preserves the property and the landowner receives money or tax benefits in return. Bequesting land in a will to a favored organization will also do the job of preservation.

Wood notes that even in rural places, historical preservation garners growth. In Charleston, Tenn., for example, the community has invested in trails and a greenway around its historical Fort Cass, which served as an internment camp for Cherokee, Creek and enslaved African Americans at the beginning of the Trail of Tears in 1838. Of the 15,000 people who were forcibly removed from their homes, it is likely that several thousand died in such internment camps or along the cruel march to their new home in Oklahoma.

History, whether good or bad, provides a sense of place. And more and more, Wood says, communities want to build their own place in history.

What Could Have Been

It winds through the rolling farmland and forests of southern Ohio, lifting just above the Earth, stretching to 1,348 feet long and weighing innumerable tons.

The Serpent Mound, under consideration for UNESCO World Heritage site status, is the world’s largest surviving example of an animal effigy mound. A huge number of original earthworks in Ohio — placed along livable rivers and arable valleys — are already destroyed.

Serpent Mound, thankfully, was protected from the get-go, says Crystal Narayana, program director for the Arc of Appalachia, which manages the site as well as thousands of acres of regional wilderness and historical sites. The mound was made a publicly-accessible archaeological park in the late 1800s, and has been in the hands of Ohio History Connection for more than 100 years. Dense forest buffers the 60 acres and a tributary of Ohio Brush Creek, home to endangered fish and mussels, from potential development.

A few earthworks exist in government or nonprofit hands, Narayana says, but many lie with private owners, who may not always have preservation in mind. Twice, she says, the Arc of Appalachia has stepped in to save earthwork sites from the auction block. Her organization, which has saved 4,000 acres of wilderness and historical sites since 1995, will soon start fundraising to buy another site back from a mining company.

“The people who live here are just not very aware of their significance, and that is unfortunate,” she says in an email.

More than 40,000 visitors come every year to Serpent Mound, a little more than an hour east from Cincinnati — which, incidentally, was built over an earthwork. Tourists at the serpentine effigy can visit a museum, walk on trails and take in the panoramic view from an observation tower.

Unlike other earthworks, Serpent Mound was not a burial site. It holds no attributable artifacts. Instead, current research suggests it may have been built to direct spirits of the dead to farther-on resting spots. Nearby conical burial mounds suggest the builders may have been from the Adena Culture or the Fort Ancient Culture, whose timeframes run separate from each other by more than a millennia.

“I think the modern people of Appalachia have a lot in common with the ancient Native Americans,” Narayana says. They lived off the land, hunted, gathered nuts and grew gardens. Native American blood persists in the region, though lessened from earlier times, and preserving this place of mystery may be just one more important step to connecting with the shared past.

Lost Time

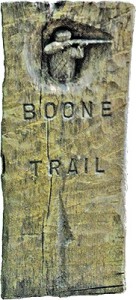

At Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, reenactors commemorate the first crossing of the gap by European settlers in 1775. The trail marker denotes the beginning of the Boone Trace pathway at the park. Sam Compton, president of The Boone Society, notes that the light striking the trees seems to form a heart above Daniel Boone. Photo by Roberta Mills, Boone Society

The race to save history has always been a race against time. Stories fade without frequent telling, and for Sam Compton, who is married to a descendent of Daniel Boone, the retelling of Boone’s story is personal.

Compton, as president of The Boone Society, wanted to make a more perpetual reminder of his backcountry legacy. Using his background as a businessman, he began the process of making a heritage trail called the Boone Trace Corridor.

The corridor of roadside stops would follow the footsteps of famous frontiersman Daniel Boone. In 1775, on the eve of the country’s independence, he was paid by the Transylvania Company to take 30 axmen and clear a path for settlers from the Cumberland Gap about 119 miles north to Fort Boonesborough, Ky.

The trail currently passes a handful of historic cities, state parks and museums. Under Compton’s guidance, and with help from more than 120 state and local partners, the path will expand to include more sites and a series of self-guided education stations along the road. “The more places that you can create within your county, [the more the tourists will] slow the traffic down and they’ll spend more money in that county,” says Compton.

A trail marker denotes the Boone Trace as it begins it’s pathway across the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. Photo by Sam Compton

Tourists are no longer the byproduct of historic preservation; they are mechanisms by which it happens. As such, Compton is focused on making an adventure of the Boone Trace. Towns and highways block a fully walkable trail such as the Appalachian Trail, but the corridor can still step off to dramatic destinations. Just off the road, beyond the education stations and history signage, visitors could step in the exact footsteps of Daniel Boone, canoe the rivers, walk the trails and take horses into the backcountry. Activity becomes meaning felt through cultural memory, and the end result is something that everyone can keep.

“There would be no Oregon Trail or Santa Fe Trail or Gateway to the West in St. Louis had it not been for Daniel Boone making those first steps,” says Compton.

He says that Boone is already vanishing from school curriculums. The Kentucky Department of Education is working on new Daniel Boone lessons, but he’s still worried that it won’t be enough.

History becomes old, tired. Kids will stop learning about Boone, and then one fine day, he’s gone. One of the society’s Boone impersonators, speaking about the disappearance of frontier history, once said to Compton, “It’s almost like God created man and then there was the Civil War.”

Like all history — that which you can still hear or feel or touch — it was and is so much more than that.

Lewis and Clark Eastern Legacy Trail:

Though still needing a final study and congressional approval, a proposed road route would follow the pair’s fascinating trip back to Monticello and Washington, D.C, from Louisville, Ky. Did you know Lewis took an astronomical observation at the Cumberland Gap in 1806? Or that Clark was a month behind Lewis because he was courting a Louisville woman?

Trail of Tears:

A section of the the Unicoi Turnpike Trail — one of the oldest known trails in North America — was used by prehistoric Americans, later tribes and European settlers before serving as part of the Trail of Tears for Cherokee and Creek tribes. A two-and-a-half mile segment of the trail was recently transferred to the U.S. Forest Service for public access and preservation.

Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail:

The Overmountain Men of the Appalachian frontier won the Battle of Kings Mountain and helped win the Revolutionary War. Nowadays, you can follow these frontiersmen’s footings through 330 miles of roadways or a separate 87 miles of walkable paths from Virginia to South Carolina. Fun enough to start another Whiskey Rebellion!

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests