AV's Intern Team | June 15, 2015 | 1 Comment

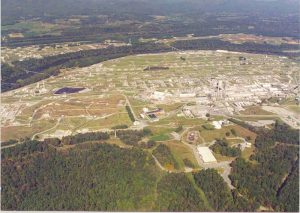

The Radford Army Ammunition Plant in Virginia manufactures munitions for the U.S. Army. Photo courtesy U.S. EPA

By Andrea Brunais

Perhaps in a parallel universe, these four things don’t sit within walking distance: a toxin-emitting munitions plant, a mountain river, an elementary school playground and Kentland Farm, where Virginia Tech students tend plots of fruits and vegetables.

The New River, famous for its snaky wildness, is a favorite of kayakers and tourism-boosters who tout its unusual south-to-north flow and its ancient origins. Biodiversity flourishes near the river, whose features include breathtaking rock cliffs and rim-top ledges. Its three-state span – North Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia – hosts vastly different environmental issues along its length.

In Virginia’s Pulaski and Montgomery counties near the town of Blacksburg, a 4,600-acre U.S. Army munitions plant dating to 1941 straddles the New River. Bill Hayden of the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality confirms that the Radford Army Ammunition Plant, operated by a private contractor to manufacture munitions for the U.S. Army, is “one of the top emitters of toxic chemicals in the state.”

According to the DEQ, some nine million pounds of toxins are released from the plant annually, most being nitrate compounds stemming from the process that neutralizes acids used to make explosives. In the agency’s Toxic Release Inventory report for 2013, issued this spring, the arsenal once again topped Virginia’s list of polluters; the annual report has frequently listed the plant.

By law, operators are permitted to discharge toxic substances, mostly nitrates, into the river. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the plant’s toxic emissions include nitroglycerin, lead, ammonia and nitric acid. Other hazardous wastes identified at the plant include remnants of TNT, chromium, cadmium and perchlorates.

The operators are also issued permits to burn some of the hazardous waste left over from the manufacturing process. Burns take place out in the open, in sight of the river and close to an elementary school. The DEQ issued a warning letter to the facility in April 2015 when an open burn produced 4 percent more lead than the permit allows.

The plant was cited as a top polluter in a 2012 report on the nation’s most contaminated waterways from the Environment America Research and Policy Center, but studies repeatedly deem the plant’s emissions — at least those that are measured — in compliance with environmental laws and health standards. Regulators from the DEQ as well as Army staff defend the strictness of the standards.

The latest all-clear regarding water quality comes from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A study released in January concluded that the plant’s discharges “cannot harm people’s health” via groundwater used for local residential drinking water.

According to Rick Roth, president of the local Friends of the New River and professor of geospatial science at Radford University, the CDC’s conclusion does not surprise him. “Are they the kind of toxins that bioaccumulate?” asks Roth of the plant’s nitrogen discharges into the New River, and immediately answers, “No.”

But according to a former Virginia DEQ employee who quit his job citing lax enforcement, concerns over the plant’s history of handling hazardous materials on the premises are legitimate.

The former regulator, who spoke on condition of anonymity, says nitrates may not measurably contaminate the river even when permitted discharge limits are exceeded because the river is huge enough to easily swallow up the compounds. But he points to what he calls a fundamental flaw in the agency’s methodology: “The DEQ’s entire approach is that dilution is the solution,” he says.

Which is better, he asks: Halting the discharge of millions of pounds of contaminants into a water body, or continuing the polluting practices because of the theory that the New River is so large and flows so fast that the toxins quickly seem to leave no trace?

Some environmental advocates believe the battleground should be air quality rather than water quality. The plant’s DEQ permit, which allows 8,000 pounds of propellant to be burned in the open air each day, is up for renewal at the end of June.

According to Peter deFur, an environmental scientist and instructor at Virginia Commonwealth University, air quality measurements in nearby neighborhoods have never been collected and are needed.

Dr. Jill Dyken — the co-author of the CDC report that examined groundwater near the plant — agrees, stating that the agency “recognizes the lack of air sampling results as a data gap.” She further writes in an email that the agency’s next step is to “evaluate the community’s exposures to contaminants in air.”

Blacksburg resident Devawn Oberlender, spokesperson for Environmental Patriots of the New River Valley, campaigns to end the arsenal’s open burns. During the burns, contaminated material is doused with diesel fuel. Plant employees go behind a wall as the burn begins.

“All of this takes place 150 feet from the New River – just a mile and a half upwind from Belview Elementary School,” Oberlender says.

On the plant’s website, the Army states that safety procedures “include red flashing lights and a warning speaker system to notify people on the river that a burn is going to occur.”

Also adding to the air pollution is an aging 1941 coal-fired power plant that generates most of the arsenal facility’s electricity. According to Rob Davie, the Army’s chief of operations at the plant, getting a new, cleaner plant within two years is one of the “priorities” of the Army.

Greg Nelson, a Virginia Tech student whose doctoral dissertation focuses on public participation in the hazardous-waste cleanup at the arsenal, seeks to address the risks from burning thousands of pounds of what are called “munitions constituents.” He says, “The health effects have never been documented because there’s never been a health study.”

According to Nelson and deFur, the half-century track record as a major emitter of contaminants provides ample reason to investigate the Radford plant for Superfund status. But the EPA-supervised cleanup plan for the facility stops short of classifying the plant as a Superfund site, and Justine Barati, director of Public and Congressional Affairs Joint Munitions Command for the Army, supports the status quo, responding in an email that Superfund status does not apply.

For Nelson and deFur, Superfund classification could be a big part of a long-term solution. According to deFur, if agency regulators were to declare the arsenal a Superfund site, a full-scale cleanup could take place with federal agency involvement “in a day-to-day way,” he says. Public scrutiny would be increased as well, Nelson adds.

What’s more, deFur says, Superfund oversight would bring more attention to groundwater cleanup. “The data on what chemicals are going where are not sufficient to confirm that the existing problem is not larger and not reaching the New River,” he says.

At a recent public meeting on May 28 mandated by the cleanup plan, Oberlender and others came armed with a December 2014 report from the EPA’s National Enforcement Investigations Center that was publicly released the day before. The report, which the Environmental Patriots of the New River Valley obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request, outlines violations of four federal statutes including the Clear Air and Clean Water Acts. When asked about the findings at the meeting, Army officials said they were not yet ready to comment.

BAE Systems, the plant’s private-sector operator since 2011, also operates Holston Army Ammunition Plant in Kingsport, Tenn., where the Tennessee Clean Water Network has filed suit against the company and the U.S. military. The lawsuit claims that the Kingsport plant is polluting the Holston River, a drinking water source, with RDX, an explosive chemical that may also be a human carcinogen.

But the Radford plant’s contamination problems predate BAE Systems by decades. Over the years, explosions and major fires have repeatedly occurred. Relatives of people working at the arsenal, who asked to remain anonymous, say the community accepted such incidents because they were thankful for jobs — even though the price paid included spills and releases of toxic chemicals into the soil, water and air.

As the June 29 deadline to begin the renewal process for the plant’s open-burn permit approaches, DEQ spokesperson Hayden says the agency is “evaluating possible alternatives.” The Army’s Davie says the arsenal “will be going to bid” on a project to design an incinerator to replace open burns, but he declines to answer questions about timeline and cost.

Different disposal methods were considered at Camp Minden in Louisiana, where a 2014 proposal to eliminate more than 15 million pounds of an explosive propellant called M6 through open burns spurred public outcry. In May 2015, the EPA approved the Louisiana Military Department’s proposal to hire a contractor to conduct a contained burn.

Oberlender has followed the events at Camp Minden and strives to see the open burns in Radford replaced with safer disposal methods.

“I think there’s more widespread challenge to [the permit renewal] coming than the Army has let on,” deFur says. “The question is, how long is anybody going to put up with the open burning and [with] Radford being one of the largest contributors of nitrogen going into the river?”

As the Army readies for the DEQ’s decision, greater public questioning has upped the ante. “They’ve never had as many people asking about the plant as there are right now,” Nelson says. “There’s more public questioning than the arsenal has ever experienced in its history.”

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests

What bothers me about articles such as your above article is that nothing is ever mentioned in articles about the arsenal about the fact that the company that runs the arsenal, BAE Systems, is a British firm. Did you know that?