Molly Moore | August 12, 2015 | 1 Comment

By Molly Moore

Residents from the greater Charleston area gather for a panel discussion regarding public water safety facilitated by Advocates for a Safe Water System in November 2014. Photo by Joe Solomon.

When two water main accidents within the space of a week interrupted water service for up to 25,000 customers this summer, West Virginia American Water took out a full-page ad in the Sunday edition of the Charleston Gazette-Mail to say “sorry” to the ratepayers who were required to either fill tubs and jugs with water, buy bottled water or do without.

The incident wasn’t the investor-owned, private utility’s first apology to its ratepayers, nor their customers’ first experience going without potable water.

In January 2014, a chemical storage tank upstream of West Virginia American Water’s intake — the only drinking water source for 300,000 residents — leaked approximately 7,500 gallons of the coal-washing chemical MCHM and 400 gallons of the chemical mixture PPH.

The licorice-scented chemical mix infiltrated the company’s water system undetected, and the resulting contamination led to “do not use” orders lasting a week or more, a state of emergency that lasted a month, and resident reports of water use leading to rashes, headaches, dizziness and other ailments for months to follow.

This June, soon after the faulty water mains were repaired, citizens filed a brief in a lawsuit regarding damages from the 2014 chemical spill. The brief stated that while Freedom Industries, the now-bankrupt owner of the leaky chemical tank, was responsible for the spill itself, “the resulting tap water loss would not have occurred but for a decades-long string of negligent acts and misfeasance by [West Virginia American Water Company] and Eastman Chemical Company [the manufacturer of MCHM].”

Adding to the public scrutiny, West Virginia American Water — a subsidiary of the national company American Water — is currently seeking state approval for a general 28 percent rate increase, including a nearly 30 percent increase for residential customers. The request, filed April 30, has attracted media and public attention toward the company’s business model and plans for infrastructure improvements. The Public Services Commission must decide whether to approve the request by February 2016.

At the end of June, Advocates for a Safe Water System, a volunteer-run citizens group that formed in the wake of the chemical spill, was granted permission to intervene in the rate case.

“We originally came together as people who were upset about being billed for contaminated water during the crisis,” says Steering Committee Member Cathy Kunkel.

The citizens group is scrutinizing the company’s plans for the more than $35 million in potential additional annual revenue from the rate increase, and is raising questions about whether the company’s long-term plans fit with the region’s water needs, or whether West Virginia residents would be better served by a public utility.

“We kept meeting, learned more, and realized the water company had been really not doing what it should to protect people from this kind of event, and we didn’t have a safe water system, which means we were still vulnerable to having something like this happen again,” Kunkel says.

Nationally, water ownership is moving toward more municipal control, according to Mary Grant, water privatization researcher for the advocacy organization Food & Water Watch. She cites data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency showing that, from 2007 to 2013, the number of U.S. residents served by water systems owned by local governments grew by 17 million, while those with privately owned water systems fell by 7 million.

Grant attributes this in part to the fact that privately owned water costs more for the consumer, because governments have access to cheaper financing and public utilities do not need to pay for investor profits and corporate income taxes. A Food & Water Watch analysis reveals that customers of private utilities usually pay 33 percent more for water and 63 percent more for sewer service than residents who rely on local government services.

In the Tarheel State, the environmental justice organization Clean Water for North Carolina has expressed concern that state policies encourage large private water companies to establish uniform prices for residents across wide geographic areas. The group adds that this can lead to low-income communities paying for repairs that don’t affect their neighborhoods.

According to Grant, the trend of transferring private utilities to public hands is also driven by the growth of cities and the fact that contracts with investor-owned water companies are often bad deals for cash-strapped governments.

The southwest Virginia town of Coeburn, Va., is one such example. Coeburn entered into a contract with Veolia Water North America, a subsidiary of a French multinational corporation, in 2009. But after financial difficulties following the Great Recession, the town council voted in 2013 not to renew the contract. At that point, the contract cost the town $1.41 million of its $1.47 million annual budget.

Coeburn had run its own public works department before the 2009 deal. “When we ran the numbers ourselves, it was about $400,000 cheaper [for the town to run the water utility],” then-mayor Jess Powers told the Bristol Herald Courier.

But regaining public control is not always so straightforward. In the early 2000s, dissatisfied residents in Lexington, Ky., attempted to replace Kentucky American Water with local, public ownership.

Citizens in favor of public purchase gathered 26,000 signatures during the summer of 2005 to put the issue on the November ballot. The water company sued to block the vote, but dropped its legal challenge the following year. During the 2006 election, the public voted to remain with the company by a 20-point margin. Kentucky American Water spent $2.71 million on the campaign, according to Food & Water Watch.

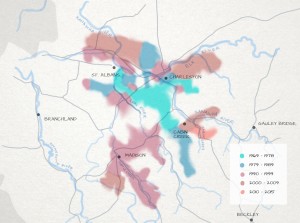

A map shows the expansion of West Virginia American Water since 1969. Click to enlarge. Created by Alicia Willett for wvwaterhistory.com

“Remunicipalization” may be the general national trend, but there are still exceptions. American Water is the largest investor-owned utility in the country. In western Pennsylvania, it has expanded service lines to reach gas companies engaging in the water-intensive process of natural gas fracking.

“As they expand to serve these gas companies, they’re also connecting households along the way who have their groundwater contaminated, possibly because of those gas drilling operations,” Grant says.

The company’s expansion in Pennsylvania due to the loss of private wells to polluted water has also occurred in West Virginia.

“One interesting thing about West Virginia is that American Water received subsidies to expand in Putnam County, but then after [the company] was denied a rate increase, it wanted to renege on those promises to expand service to areas where household wells had been contaminated … by the coal industry,” Grant says. Ultimately, the state ruled that the company had to expand services to the affected areas.

Between 2004 and 2009, local groundwater and household wells were contaminated in Boone County, W.Va., when coal slurry — a toxic sludge that remains after washing coal — was injected into abandoned underground mines. In 2009, a state moratorium on underground injections took effect. Also that year, a partnership between Boone County and West Virginia American Water used $1.5 million from a federal grant, combined with smaller contributions from the county and company, to expand the company’s service to residents of the town of Prenter, 35 miles south of Charleston.

“So we got city water up here, and it took them two or three years to get it up here,” Prenter resident D.J. Estep told Gabe Schwartzman, a fellow at University of California – Berkeley who researched and wrote the website wvwaterhistory.com. “And then a year later the MCHM spill happened. And we were stuck. Now it’s like you’ve got to choose between two evils. The one you’re used to and the one you’ve got.”

Expansion to serve remote communities with polluted water explains just one part of the growing number of customers served from the Elk River intake. On his website, Schwartzman, also a member of Advocates For A Safe Water System, describes how West Virginia Water Company, the predecessor to West Virginia American Water, built its large Elk River intake in 1976 with the intention of serving industrial customers. Those customers didn’t materialize, he writes, so in the ‘80s the company “launched an aggressive expansion strategy, pushing to take over small municipal systems and public rural systems.”

In 1994, the Charleston Gazette reported on the company’s effort to expand to the town of Clendenin. At a meeting, then-president of WVAM Chris Jarrett told town council members, “It is simply more efficient and more economical, the more customers you can serve from one large production facility.”

A single intake might be cost-efficient, but the Elk River chemical spill in January 2014 displayed the pitfalls of reliance on one facility. And it turned out that, to save money, West Virginia American Water Company had sold its chemical monitoring equipment upstream of the Elk River intake in 2004. A new chemical monitoring system wasn’t installed until after the 2014 spill. The new equipment falls short of being able to detect MCHM and a host of other chemicals — technology that is in use at major water plants around the region — according to a chemist and a chemical engineer who are also members of Advocates for a Safe Water System.

A state investigation into West Virginia American Water’s response to the spill is currently stalled until Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin appoints another member to the three-person commission.

According to a utility press release, the company’s request for a 28 percent rate increase is driven by “the approximately $105 million of system improvements the company has made since 2012 as well as an additional $98 million that the company plans to expend on recurring and investment projects through February 2017.” The rate hike would also increase the West Virginia subsidiary’s profit margin from 4-5 percent to 10.75 percent.

Cathy Kunkel of the citizens’ group claims this is at odds with customers’ experiences. “You say you’re raising rates due to major capital expenditures you’ve made, but it doesn’t seem like we’re benefiting from them,” she says.

In the Frequently Asked Questions section of its website, the company acknowledges that it is replacing infrastructure at the rate of once every 400 years, but notes that rate is faster than it had been, and that the the cost of reducing that replacement cycle to 100 years — the target rate — would place heavy costs on ratepayers.

Yet Kunkel is concerned that replacing water mains will not be a priority, despite this summer’s repeated breaks. Advocates For a Safe Water System has also proposed construction of a reservoir to serve as an alternate water source for Charleston and the surrounding area, a plan that the water company has not publicly considered.

When asked what an ideal water system would look like, Kunkel is clear.

“Fundamentally, it needs to be transparent — people need to have a clear idea of how the water system is making decisions with our money,” she says. “[It needs to be] responsive to citizen concerns, and it needs to be fair. People should get the service that they’re paying for.”

UPDATE: In September 2015, after this article was published, Advocates for a Safe Water System launched a campaign for a public water system to replace West Virginia American Water. Learn more at ourwaterwv.org.

Discover maps and more information about the history of West Virginia American Water, and hear audio clips from West Virginians regarding the impact of the 2014 chemical spill at wvwaterhistory.com. The multimedia website, authored by Gabe Schwartzman with web and graphics by Alicia Willett, was created with support from the Judith Lee Stronach Baccalaureate Prize at the University of California-Berkeley.

“You can just see how being poor affects you when there is a crisis. The initial places for the water distribution were such that if you didn’t have transportation it would be hard for you to get water because you could only carry it so many blocks. We believe that many people in this community probably did use the water when they were advised not to use it, because they just could not get enough water.” — Pastor Michael J. Watts, Grace Bible Church of Charleston, W.Va. “It was during the early 1980s when … [West Virginia American Water] did take over many systems were near the brink of failure. Many of those systems were not economically viable, with the changing in water economy over the years. The Putnam System was economically viable, and one of the few areas where it would have been profitable for them to take over the system. So they were very aggressive and approached us in a very hostile manner.” — Fred Stottlemyer, former director of the Putnam Public Service District, which is still community owned and operatedLike this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests

Publid Service=Socialism, Self-Service-Privatezation