A new pumped storage energy facility in Southwest Virginia could potentially reuse an old coal mine — or raze a hillside

Kevin Ridder | December 6, 2017 | No Comments

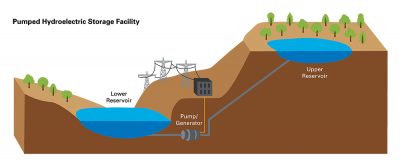

At first glance, pumping millions of gallons of water uphill to later release for energy may seem like a senseless use of energy. But pumped storage can actually bring much-needed stability to the grid or balance out wind and solar’s inconsistent energy generation.

The relatively small exterior of the Bath County, Va., pumped storage facility belies its status as the largest of its kind in the world. Photo courtesy of Dominion Energy

A community’s energy usage typically ramps up in the morning, peaks in the early evening and falls as people go to sleep. When more power is being produced than used, a pumped storage plant could use that extra energy to pump water uphill — and then reverse the process to generate energy during a time of peak energy usage, serving as a massive battery.

Appalachia is already home to the Dominion Energy’s Bath County Pumped Storage Station in Virginia, the world’s largest pumped storage plant at 3,003 megawatts. Now, Dominion is exploring the possibility of another, smaller plant in the coal-bearing region of Southwest Virginia.

This comes after two bills (HB 1760 and SB 1418) backed by Dominion and Appalachian Power promoting pumped storage projects became law on July 1. The legislation speeds up the approval process for a pumped storage project — as long as it is “in the coalfield region” — and allows the utility to petition the Virginia State Corporation Commission for a consumer rate hike to pay for it. It also declares the construction of pumped storage facilities “to be in the public interest.”

“It ends up creating an essentially zero-risk proposition for Dominion,” says Matt Wasson, director of programs for Appalachian Voices, the publisher of this newspaper. “Their ratepayers are basically taking all the risk.”

According to a September Dominion press release, the company is looking at two possible sites for the potential $2 billion proposed project: a 4,100-acre Dominion-owned site in Tazewell County and the abandoned Bullitt Mine site in Wise County, which Dominion would need to purchase. Other sites have not been ruled out.

“Dominion Energy filed a preliminary permit with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) for the Tazewell location on [Sept. 6],” the release states. “The company has contracted with Virginia Tech to conduct the study of the former Bullitt Mine near Appalachia, Va.”

In an October Coalfield Progress article, Stuart Burrill wrote “[Dominion] officials said they expect the Bullitt site, if used, would generate about 100-150 megawatts.” The preliminary Tazewell permit proposes a 446-megawatt capacity.

According to Dan Genest with Dominion, the smaller energy potential at the Bullitt site stems from the need for smaller equipment and a shorter elevation drop.

A study performed by Chmura Economics and Analytics and commissioned by Dominion states that a $2 billion project over 10 years would “support a total of 86 jobs annually in the state,” with 76 of those in Southwest Virginia. The facility would be “expected to employ about 50 permanent workers.”

“We hope to have a decision on the preferred site, and whether to move forward, by the end of the first quarter of 2018,” David Botkins of Dominion Energy wrote in an email. “It would take 10 years before the facility could be in commercial operation.”

Pumped storage can be thought of as a giant rechargeable battery — pumping water uphill when there’s extra energy being produced, and letting it flow downhill to generate energy when needed. Image courtesy of Dominion Energy

According to LeRoy Coleman with the National Hydropower Association, a nonprofit that promotes hydropower, several pumped storage projects are built on mines — but a project on the Bullitt site would be the first in the nation on a coal mine.

Gabby Gillespie, Southwest Virginia organizing representative for the Sierra Club, is unsure about the possibility of a pumped storage project in her home of Wise County. She says she hopes “that this project would require some form of environmental impact study or assessment” in addition to the feasibility study being conducted by Virginia Tech.

“Anytime that we’re using underground mines, especially when pumping water into them, I do think we need to consider the impacts on our water and the impacts of continuous disturbance of formerly mined lands,” Gillespie says. “That’s a practice I haven’t seen a lot of research about.”

Virginia U.S. Rep. Morgan Griffith introduced a bill in June that would loosen the regulatory process for closed-loop hydro projects, like the potential venture on Bullitt Mine, that don’t connect with an existing, naturally flowing water source.

“H.R. 2880 removes environmental impact statements for closed-loop pumped storage hydropower projects that are determined not to affect animals and plants,” Rep. Griffith said in an email statement.

The Tazewell County site would need to have environmental impacts taken into consideration, according to the preliminary permit application. It would connect with West Fork Cove Creek.

Peter Anderson, Virginia program manager at Appalachian Voices, has concerns about a potential project on undeveloped land when there are plenty of properties with past industrial infrastructure or mined lands that could be reclaimed.

“What you’d be doing is razing lands to build an upper reservoir and a lower reservoir, probably a lot of tree and vegetative removal,” Anderson says. “You have to do this on a hillside, you need a change in elevation. You’re probably cutting down a lot of trees, creating a lot of sediment runoff and erosion problems.”

Jeff Leahey of the National Hydropower Association says he sees the need for pumped storage projects increasing “because of the greater amount of penetration of solar and wind resources.”

“I would say that by putting more pumped storage on the grid, ultimately what you’re doing is enabling your grid system to be more robust in order to bring more renewables and to green up the grid,” Leahey says.

One of the recent Virginia laws promoting pumped storage requires that these potential projects “utilize on-site or off-site renewable energy resources as all or a portion of their power source” and that those renewable resources be “located in the coalfield region of the Commonwealth.”

Anderson says, “it’s an exciting possibility if you were to power one of these things with 100 percent renewable energy,” but that the law is not specific enough.

“What does ‘a portion of’ mean?” he asks. “Does that mean one percent? Twenty percent? That could mean anything.”

In the Virginia code, the burning of biomass counts as renewable energy — meaning it could be used to fulfill this requirement instead of solar or wind.

“Bottom line is: will they use this as an opportunity to build storage for energy that is truly renewable and do it in a way that builds community wealth?” Anderson says. “Or, since they know the ratepayers are going to pay for it, will the utilities just use this new authority to build large infrastructure that doesn’t advance conservation in any way and simply stores coal and biomass power?”

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests