If our representatives in Congress fail to act before next year, a fund supplying health care for coal miners diagnosed with black lung disease will be put in danger.

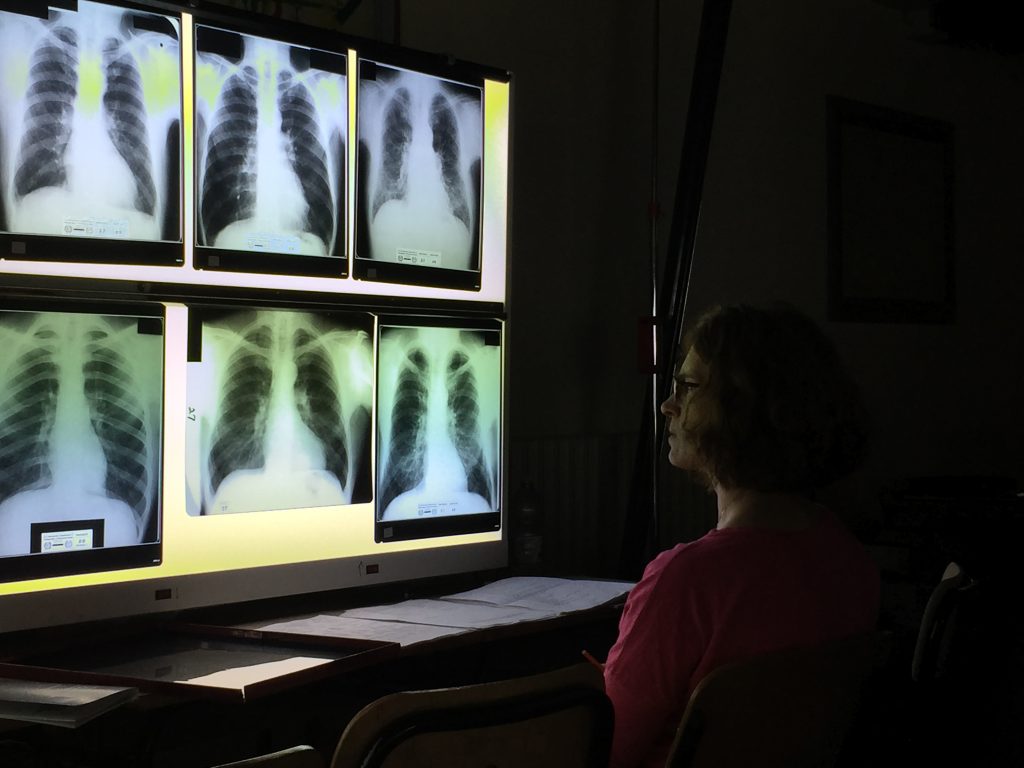

A participant in a course that certifies physicians to spot black lung symptoms evaluates various chest x-rays. Photo courtesy of CDC-NIOSH

Coal companies are currently taxed $1.10 for every ton of underground coal mined and 55 cents for every ton of surface coal mined to finance the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund. But in 2019, those rates are scheduled to drop to 50 cents per ton and 25 cents per ton, respectively.

The fatal, incurable disease is caused by long-term exposure to coal and silica dust in and around coal mines, and is estimated to have killed more than 76,000 people since 1968. Today, one in five Central Appalachian coal miners who have spent 25 or more years working underground suffer from black lung, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health in August.

“We can think of no other industry or workplace in the United States in which this would be considered acceptable,” the study’s authors wrote in the journal.

The rise in black lung isn’t limited to underground coal miners, either. A 2012 study examining black lung in surface miners found that the prevalence of progressive massive fibrosis — the worst form of the disease — had reached 0.5 percent, five times higher than reported in a similar study in 2003.

On Aug. 14, the Big Stone Gap, Va., town council unanimously passed a resolution in favor of keeping the tax on coal companies at its current level. It is the first town in the nation to do so.

“Just about anybody in this part of Southwest Virginia has some association with black lung,” says Big Stone Gap Councilman Tyler Hughes. “It could be somebody in their family, in their friend group, or somebody that they professionally work with.”

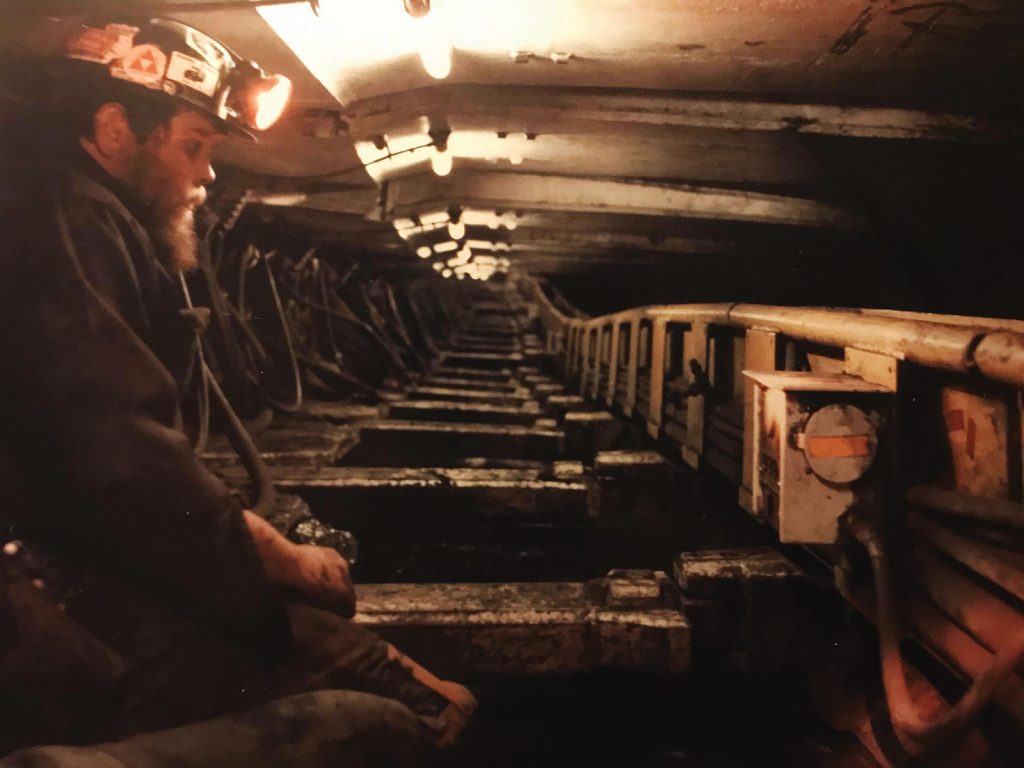

Ed Rich, Councilman Tyler Hughes’ grandfather, on the longwall in Westmoreland’s Bullit Mine in Wise County, Va., circa 1986. Mr. Rich is now retired and living with black lung. Photo courtesy of Ed Rich

“It’s not only a moral issue that a company takes care of its workers, but it’s also an economic issue,” he adds. “We live in a really impoverished portion of the commonwealth. And most people, regardless of where they live, have trouble paying for their healthcare whether they have black lung or not. And we know that the treatment of black lung is very expensive, so we’re asking men and women who are already probably living on fixed income — more than likely having to stretch every penny — we’re asking them to take on an even larger burden. And if this fund goes away, that’s only going to grow their troubles.”

National Mining Association President Hal Quinn, however, appears to view the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund as a financial burden on coal companies. “Changing the schedule now would effectively impose a tax increase on an industry struggling to recover from the regulatory excesses of the past administration,” Quinn wrote in a June 2018 letter to two key U.S. House members, according to Reuters. Additionally, the letter reportedly stated that black lung disease was in decline — a claim that can be quickly disproved by anyone with access to Google.

In February, researchers published findings that 416 coal miners were diagnosed with progressive massive fibrosis in three Southwest Virginia clinics operated by Stone Mountain Health Services between 2013 and 2017. The authors stated that this is “the largest cluster of [progressive massive fibrosis] reported in the scientific literature.”

From left to right: a basically normal human lung; a lung with coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, also known as black lung disease; a lung with coal workers’ pneumoconiosis and progressive massive fibrosis, also known as severe black lung disease. Photos courtesy of CDC-NIOSH

Ron Carson, the former director of Stone Mountain Health Services’ black lung program and a co-author of the findings, told NPR that in the 1990s he would see five to seven cases of progressive massive fibrosis a year. Today, he said the clinics meet that number every two weeks.

“That’s an indication that it’s not slowing down,” Carson told NPR. “We are seeing something that we haven’t seen before.”

Progressive massive fibrosis has grown as a whole, according to an August study. In 2014, 8.3 percent of miners filing for black lung benefits had the advanced stage of the disease, compared to 0.6 percent in 1988. The problem is largest in Central Appalachia; 84 percent of miners with progressive massive fibrosis last mined coal in West Virginia, Kentucky, Pennsylvania or Virginia.

Councilman Hughes is alarmed at the increasing prevalence of the disease.

“It is quite worrisome to think that, at a time when we are looking for jobs in the coal industry, to know that some of the risks associated with the industry are starting to grow,” he says.

Hughes has seen the toll black lung disease takes firsthand. His grandfather, a coal miner for more than 30 years, suffers from the condition.

“To see my papaw go from somebody who loves hunting and fishing and going to the flea market and doing all the things he loves, to now having to have a portable oxygen tank and losing his breath when he walks from the truck to the front door; that’s really heartbreaking to see that sort of freedom and enjoyment of his life taken away from him because of this disease,” he says.

Big Stone Gap, Va., Councilman Tyler Hughes asks the town council of Pennington Gap, Va., to pass a similar resolution supporting the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund. Photo by Gabby Gillespie

Hughes hopes to see similar resolutions from other Central Appalachian communities in the coming weeks.

“Here in Southwest Virginia, we are just a few miles from Kentucky, a few miles from West Virginia and a few miles from Tennessee — all of which have had coal mines and the coal industry prevalent in their economy and their society,” Hughes says. “We want to see these things cross the state line because there are more than just Southwest Virginians represented in Congress. Each of our states have men and women that are supposed to be there voicing the opinion of their communities as well.”

Correction: This article was updated on Sept. 19, 2018, to clarify that that the resolution passed by the town council of Big Stone Gap, Va., supports keeping the tax on coal companies at its current level, not keeping the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund at its current level.

As a U.S. Health Officer I interviewed in-person some 90 Black Lung survivors. My impression was that, to a man, these people were misled on the hazards of their work.

I have sent emails to my lawmakers supporting the black lung miners; trying to help miners receive black lung benefits.

Many coal miners in Eastern KY complained that money was set aside for black lung miners in the past, but the bulk of that money went into the pockets of lawyers. So many underground miners see legislation to give more money to black lung miners to go into the pockets of lawyers; so those coal miners do not support future legislation for more money to black lung miners, because they see the bulk of that money going into the hands of lawyers.

Tax payers should not have to raise money to support black lung miners, the coal companies should be made to do that. But tax payers probably will end up paying black lung miners, as well as cleaning up the environment from mining.