Even within the boundaries of Daniel Boone National Forest, Copperas Fork flowed a bright yellow in July 2019 due to acid mine drainage from Revelation Energy’s Greenwood permit.

In the Daniel Boone National Forest of McCreary County, Ky., Copperas Fork and its tributaries often run a bright orange due to acid mine drainage (AMD) originating from the mined land upstream owned by Revelation Energy.

For the past few years, volunteers Teri Blanton and Joanne Hill have been testing water quality at Copperas Fork through The Alliance for Appalachia’s Appalachian Citizen Enforcement Project, which facilitates water quality testing of public waterways below surface coal mines. Following some initial water testing, Joanne and Teri informed the Kentucky Energy and Environmental Cabinet’s Department of Natural Resources of the AMD problem in Copperas Creek.

AMD is formed by the oxidation of sulfur compounds like pyrite in shales and coal. Mining exposes these shales to oxygen and water, which begins a series of chemical reactions that create sulfuric acid and lowers the water’s pH. The sulfuric acid then picks up trace metals from the rocks as it travels — usually iron, manganese and aluminum. As the solution travels downstream, the pH rises as the acid-laden water mixes with other freshwater. When the pH hits a critical threshold above 3.5, ferric iron precipitates out of the solution giving the water the characteristic yellow and orange color that we see. While the amount of AMD depends on many factors including the amount of exposed pyritic material and length of time that it is exposed, once AMD seeps begin they can last for decades, causing environmental harm and saddling local residents with unhealthy, contaminated water.

Citizen water monitors Joanne Golden Hill and Teri Blanton at Copperas Fork in Daniel Boone National Forest.

Federal mining law gives citizens the option to accompany an inspector on a mine site inspection that results from their complaint. Joanne, Teri and I accompanied the mine inspector onto the two permits that make up Revelation’s Greenwood processing facility on May 1, 2019. While on our citizen inspection, we saw several sets of ponds with the characteristic orange color of acid mine drainage. Those ponds were not discharging at that time and the inspector informed us that Revelation was actively pumping the ponds into an upper reservoir, essentially forming a closed loop to prevent water from leaving the site.

This system in no way treats the AMD — it only prevents contaminated water from flowing off-site. But the system complies with the law and prevents violations as water needs to flow from the pond into public waterways before it is subject to water pollution laws and specific contaminant limits. If the pumps were to stop working, the ponds would overflow and discharge acid mine drainage into the streams below. It was obvious from the spillway of pond 13 that this had happened in the past.

Map shows Revelation Energy’s Greenwood permits.

Though we had tested the creek’s water quality downstream on national forest land, the inspectors would not let us take our own water samples on the mine site. We were told a hydrologist would sample any location that we asked him to during the course of the inspection, which proved to be true. However, despite filing a Freedom of Information Act request back in May we have not yet been able to obtain the information the hydrologist collected nor his final report from that day.

On July 1, a few months after the inspection, Revelation Energy and its partner organization Blackjewel declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy, retroactively yanking paychecks from the bank accounts of hundreds of workers (sparking an ongoing protest) and raising questions about how the companies would cover their those debts as well as environmental cleanup and other obligations.

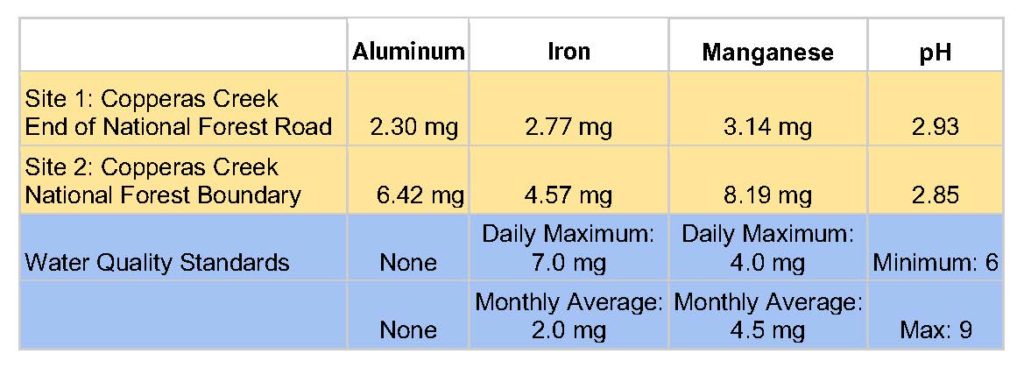

Three weeks later, the creek was running more orange than usual. I did some follow-up water testing in the national forest, and Teri Blanton called the inspector again. The inspector found that Revelation was discharging substandard water from their ponds into tributaries of Copperas Fork and then issued two imminent harm Cessation Orders and two Failure to Abate Cessation Orders to the company. Our own lab testing results also showed manganese and pH levels outside of acceptable levels in the stream.

Sources: Water testing lab results from PACE Analytical on samples obtained in July 2019. National Permit Discharge Elimination System permits for Revelation’s Greenwood mines.

It is unclear what impact these cessation orders will have on the site as Revelation is still in the middle of its bankruptcy proceedings. Still, this acid mine drainage violation highlights several concerns related to reclamation, bonding and bankruptcy. Revelation and/or Blackjewel mine permits might go into bond forfeiture, which means the companies would forfeit their reclamation bonds and leave the state to clean up the mine sites and any related water pollution problems.

While the Revelation/Blackjewel court docket has been open to the public, the auction of assets is occuring behind closed doors, leaving it unclear specifically which permits were sold and the fate of those that were not. In one court document, Indemnity National Insurance, a surety company that objected to the sale of some of Revelation’s assets, stated that the environmental liabilities — in this case thousands of acres of unreclaimed mined land — were treated as if they had zero value when the sale was considered and that state regulatory authorities could be on the hook for hundreds of millions of dollars. The document went on to say that after the auction had concluded, there was $220 million worth of bonding liability remaining on unsold permits.

At this stage it is difficult to say with certainty if these two permits at Greenwood will go into bond forfeiture. We are aware of only a handful of buyers who possibly purchased mines in Wyoming, Virginia and Kentucky, but it is unclear what will happen to the mines that were not purchased and which mines those were. The two Greenwood permits are bonded by Lexon Insurance Company at just under 3 million dollars.

Appalachian Voices Central Appalachian Environmental Scientist Matt Hepler with a water sample from Kentucky’s Copperas Fork.

Still, bonding does not always cover the cost of reclamation liabilities. A 2017 report from the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) found that Kentucky’s bonds only covered a little over 50 percent of the actual costs associated with mined land reclamation. In January of 2018, OSMRE approved changes to Kentucky’s bonding programs. However, the agency did not approve of Kentucky’s current bonding approach as it relates to the long-term treatment of mine drainage.

Kentucky bases its bond amounts on an assumption of 20 years of water treatment, but the federal agency found that Kentucky did not demonstrate that the 20-year benchmark would be adequate to protect water quality, so did not approve that portion of the regulatory changes. Tennessee, where the mine reclamation program is managed by the federal government, maintains a separate fund for water quality issues like acid mine drainage based off of an assumption 75 years of water quality treatment. OSMRE went on to say that the law does not “provide any exceptions to the requirement to post a bond that is fully adequate to cover the cost of reclamation, including water treatment.”

Kentucky does not have a federally approved long-term water treatment plan in case places like the Greenwood processing plant go into bond forfeiture. A recent report from The Alliance for Appalachia outlines that Kentucky and other Central Appalachian states have insufficient bonding mechanisms to deal with the declining coal economy and widespread bankruptcies of many mines at once. Revelation Energy is one of several coal companies to go bankrupt in the past year, andthere is still a lot of uncertainty about what will happen next.

“I am very concerned about this bankruptcy and the impacts it will have on the streams and wildlife in the Daniel Boone National Forest,” Joanne says. For now, Joanne and Teri can only wait and see how the bankruptcy plays out — and keep a watchful eye on Copperas Fork.

Helping workers affected by the bankruptcy

Water pollution is just one of the uncertainties caused by the Blackjewel/Revelation bankruptcy. The companies clawed back paychecks from employees’ bank accounts and took the unusual step of suddenly closing their mines. For several weeks, mine workers and their supporters have been blocking a Blackjewel coal train in Harlan County from transporting coal until the miners are paid what they are owed.

Community organizations like AppCAA and Harlan County Community Action have been organizing support for the hundreds of mine workers and their families who are struggling. Donations of food and products such as toilet paper, toothpaste, diapers, shampoo, laundry detergent, and school supplies are needed, as are gift cards to grocery stores and gas stations. Donated items can be dropped off at AppCAA offices in Gate City and Jonesville, Harlan County Community Action, local Powell Valley National Bank branches, or at the Appalachian Voices office in Norton. Please call ahead to make sure someone is there. You can also deposit funds into the C.O.A.L. For Miners account at any Powell Valley National Bank branch, or donate to a fund online here.

Read More

Leave a Reply