Kevin Ridder | October 11, 2019 | No Comments

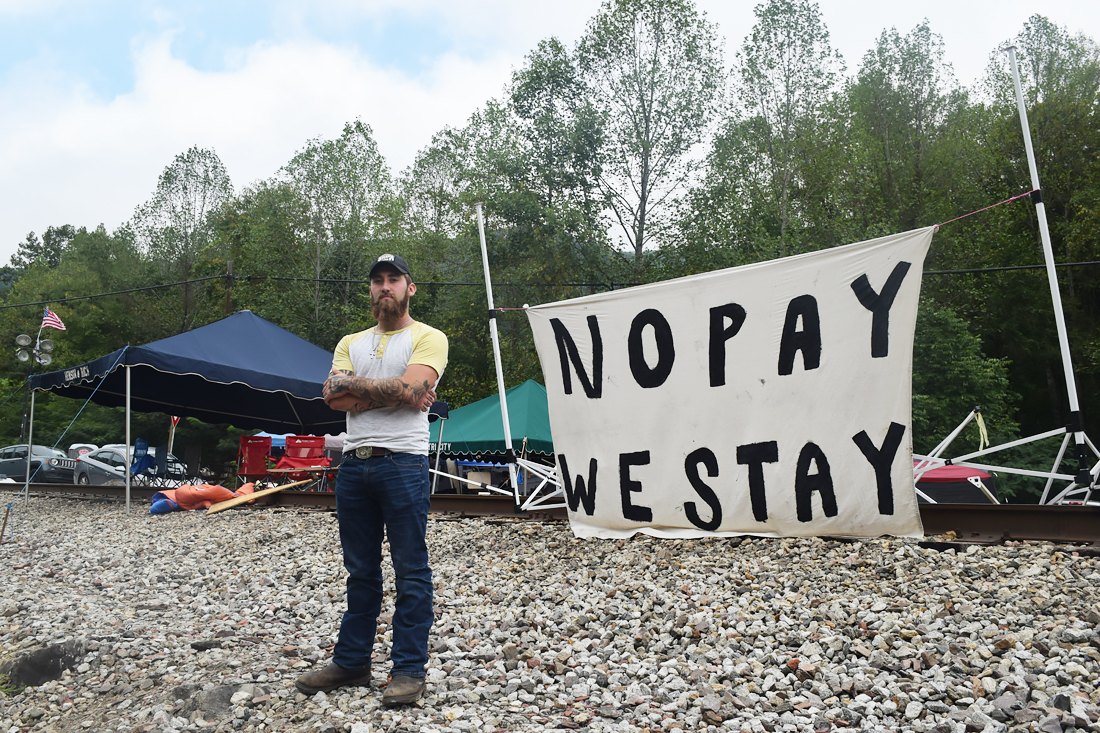

Former Blackjewel coal miner Blake Watts stands by the blockade in Harlan County, Ky., on Sept. 5. Photo by Kevin Ridder

Update: Oct. 24, 2019

Blackjewel, LLC has agreed to pay approximately $5.1 million in back wages to its former employees in Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia, according to the Lexington Herald-Leader. Of that, $1.99 million is alotted for about 400 Kentucky miners, $2.72 million for about 600 Virginia miners, and $369,000 for about 80 West Virginia miners.

The Herald-Leader reports that once the miners are paid, Blackjewel will be allowed to move the train of coal that was physically blocked by a nearly two-month long protest and later legally blocked by the U.S. Department of Labor.

A Blackjewel attorney told the Bristol Herald Courier that paychecks are expected to be issued this week, and will cover unpaid wages earned between the period of June 10 and July 1.

“The fact that the checks are presumably in the mail and won’t be clawed back does not end the litigation against [former Blackjewel CEO Jeff Hoops] individually and his coal company Lexington Coal,” said Ned Pillersdorf, an attorney representing the former Blackjewel miners, in a statement.

By Kevin Ridder

A nearly two-month long protest by laid-off coal miners in Harlan County, Ky., came to an end on Sept. 26. After Blackjewel, LLC and its affiliate Revelation Energy suddenly declared bankruptcy and retroactively withdrew paychecks in early July, a group of miners, their families and supporters stood in front of a trainload of coal that they had mined and not been paid for.

Blackjewel and its related companies operated coal mines in Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia and Wyoming and employed roughly 1,700 miners, including more than 1,100 in Central Appalachia. Many coal companies have gone out of business in the last few years — but this time was different.

“Every miner that worked for the company had their last paychecks pulled out of their accounts, leaving a lot of people anywhere between $1,500 to $3,000 in the negative,” says former Blackjewel miner Chris Rowe. “And then the last six days we worked, we never even received a check for.”

From left to right: Darrell Raleigh, Donna Raleigh, and Chris Rowe on the morning of Sept. 5 at the Harlan County blockade. Photo by Kevin Ridder

On July 29, word got out that a train was coming to move $1.4 million worth of coal in Harlan County that Blackjewel employees had mined without pay — so Blake Watts and four other former Blackjewel miners set up camp in the train’s path.

“We decided that if they were going to take that coal and not pay us, then that’s not right,” says Watts. “We worked for that coal and we deserve our pay.”

It’s not the first time Harlan County miners have taken a stand against the coal industry — in the 1930s, a series of strikes, armed skirmishes and more took place between coal miners and law enforcement and security firms hired by coal companies.

Watts is one of the few who found mining work after the company shut down, but he now drives 45 minutes to work each day instead of five. Some have moved to Alabama to find coal jobs. Others have found work outside the mines, and some have decided to change careers completely.

The former Blackjewel miners and their families often played cornhole on the railway tracks during the blockade. Photo by Kevin Ridder

“Not only did he put us out of work and call our checks back, but even after the fact we were not allowed to sign up on any kind of unemployment or anything because the company was still saying that we were employed,” says Chris Rowe. “So we went probably three weeks to a month before we could even sign up on unemployment.”

Rowe, who received multiple job offers during the blockade, has since taken a job as a truck driver. He was one of the first miners on the tracks and was the last to leave along with his wife Stacy, WYMT reports.

In July, attorneys representing former Blackjewel employees filed a class-action lawsuit against Blackjewel asking for an undetermined amount in damages. No court date was set as of press time.

The U.S. Department of Labor has labeled the train cars of coal in Harlan County as “hot goods” due to the unpaid wages, and a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order on Aug. 23 preventing the coal from being transported until bankruptcy proceedings move forward. The judge gave the agency and Blackjewel until Oct. 1 to submit arguments as to whether the coal should be allowed to be sold before the miners are paid.

In mid-September, Blackjewel issued final paychecks to the several dozen miners who worked at a mine in Fayette County, W.Va. Approximately 1,000 miners in Kentucky and Virginia have yet to receive their checks as of press time in early October, although a deal between the Department of Labor and a company associated with Blackjewel bodes well for the laid-off workers. A federal judge approved the sale of two Blackjewel mines in Wyoming on Oct. 3, finalizing an agreement that includes $5,475,000 in back pay to the workers. In exchange, the agency would allow the trainload of Harlan County coal to be sold.

From July to late September, the cluster of tents and camp shelters next to U.S. Route 119 served as a sort of second home for many of the laid-off Harlan County miners. Several picnic tables covered with newspapers and coloring books sat beside a makeshift kitchen, and the miners and their families would often gather around a car radio to listen to bankruptcy proceedings.

Former Blackjewel miner John Cress and his wife Felicia pass the time at the Harlan County, Ky., blockade on Sept. 5. Photo by Kevin Ridder

Support from near and far poured in for the out-of-work miners at the blockade. Harlan County donated a generator, lights, portable toilets and a dumpster to the camp. Food donations included canned goods and an unexpected shipment of 100 watermelons and about 30 pounds of bacon.

“When we first started, all we had was a case of water and a box of pizza,” says Rowe. “As the days went on, more donations came in, people started donating these tents, so we just started setting up camp.” Speaking at the camp in early September, he described it as “a home outside of home.”

Soon after Blackjewel announced bankruptcy, former coal executive Richard Gilliam also donated $2,000 to each of the 1,700 laid-off miners.

Duffield, Va., resident Laura Gilliam, a home health nurse and volunteer with the Appalachia Community Action & Development Agency, or AppCAA, has helped to raise more than $100,000 for the miners and their families by traveling around the region and asking for help from municipal governments. Buchanan County, Va., donated $70,000 after listening to Gilliam speak. Tazewell County, Va., funded $25,000, and the Tazewell Board of Supervisors collectively donated $200 to each miner from their personal accounts.

Larah Helayne and Pierceton Hobbs, both members of youth organization The STAY Project, at the blockade on July 31. Photo by Lou Murrey

“We’ve been paying electric bills, water bills to all the miners, and then we’ve been taking up donations, food, toiletries, house supplies — everything,” Gilliam says.

“I try to reach out to those counties in need and go up there once a week, once every other week or so and take supplies or whatever I can,” she adds. “Somebody’s got to be the mouth of the South.”

Sheldon Bush is one of several Claiborne County, Tenn., residents who lost his job when Blackjewel shut down. He states that he knows of five or six others who lived in Tennessee and commuted to a Blackjewel mine in Virginia, and that the unemployment benefits in Tennessee are much worse than Kentucky or Virginia.

He worked at a factory nearby in the weeks following the bankruptcy, although it paid $6 less an hour, before securing a job at a Kentucky mine.

Bush, who has worked nearly 30 years in the mines, calls the Blackjewel shut down “a rude awakening” and states that bankruptcies just seem part of the norm now.

“When these coal places shut down, it’s hard on communities; businesses close,” says Bush. “These small communities thrive on coal. And once it’s gone, the community dries up.”

Former Blackjewel employee and Pound, Va., resident David Phillips recalls that mine management was vague the day that the companies filed for bankruptcy.

“They said that they were going to work through it, and nobody was going to get laid off or anything like that, we were just going to work through the bankruptcy,” says Phillips. “Well, we went underground, and we were probably under there almost three hours, and they told us to come outside and that nobody was to be on the premises.”

Managers then told the miners that they would return to work on Monday, July 8, according to Phillips. But while he was vacationing with family for the 4th of July, Phillips discovered that his account balance was negative $1,900.

“Luckily I was with my parents, and they helped us get back home,” he says.

In early August, Tennessee-based Kopper Glo Mining successfully bid nearly $54 million for several Blackjewel mines in Virginia’s Wise and Lee counties and Kentucky’s Harlan and Letcher counties. The sale was approved by the court on Sept. 17, and the terms of the sale included a minimum payment of $450,000 to compensate the laid-off Blackjewel miners, with the possibility of up to an additional $550,000 from future coal revenues over the next two years.

Phillips and others hope that they can soon get back to work under the new company.

While some former Blackjewel miners have moved to find mining jobs, Phillips does not want to uproot his family and has taken up odd jobs here and there in the meantime. He says that if not for his parents and his wife’s job, they would have lost the house.

“Having to struggle trying to get our kids new school clothes and stuff like that, it just shows you that companies now, they don’t care about their people,” he says. “And [former Blackjewel CEO Jeff Hoops] didn’t care about us or he would’ve took care of us. We were just there to make him money, he didn’t care one bit about us at all. We were just a number to him.”

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests