Dan Radmacher | February 25, 2020 | No Comments

Census workers will only visit residences in person if the household does not respond to repeated mailings. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Census Bureau

Money and power.

Those are the stakes for residents of Appalachia as the U.S. Census Bureau conducts the 2020 decennial census — which will help determine how roughly $1 trillion in federal funding is distributed over the next 10 years as well as which states lose congressional representatives and which gain them.

“The Census count guides federal funding for more than 300 programs,” says Kelly Allen, West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy’s director of policy engagement. Those programs include school lunches, food stamps, children’s health insurance, Head Start, Medicare, Medicaid and the Low-Income Energy Assistance Program, among other services such as roads.

Because the population across Appalachia has stagnated or declined, the 2020 Census will likely result in the loss of congressional representation. According to a study by Election Data Services, states that include portions of Appalachia are likely to lose representatives — including New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Alabama and Ohio.

These stakes make getting an accurate count vital for Appalachian residents and communities, according to Julie Zimmerman, professor of rural sociology at the University of Kentucky.

“The decennial Census is as close as we get to knowing for sure how many people are living in the U.S. and where,” Zimmerman says. “If this isn’t accurate, it has a domino effect for so many other types of data, for funding, for the ability to make good decisions based on the actual data. In some ways, this is the most fundamental count. The ripple effects are absolutely enormous.”

An undercount of the population could cost Appalachian communities billions of dollars of federal funding.

“We’ve estimated that West Virginia could lose $188 million over the 10-year life of Census data with just a 1 percent undercount,” says Allen. “There are areas in West Virginia with Census response rates under 75 percent.”

Areas such as those are classified by the Census as “hard-to-count” areas. One-fourth of West Virginians live in hard-to-count areas, Allen says, higher than any other part of Appalachia.

There are many reasons that Appalachians are harder to count, according to Zimmerman. The region is largely rural — and 79 percent of hard-to-count areas are rural. “That means a higher incidence of people with lower incomes, sometimes with no phone or internet access,” Zimmerman says.

The lack of broadband internet access is especially important this year as the Census Bureau shifts to encouraging people to fill out Census forms online for the first time.

“That works great if you have access to the Internet or broadband service, but you can’t assume universal access in rural areas like Appalachia,” Zimmerman says. “If you don’t have access to the internet, know that Census workers will be following up.”

Residents will also be able to respond by phone, according to Timothy Maddaloni, assistant regional Census manager for the Philadelphia Regional Census Center. “We’ve also been partnering with local libraries, universities and schools to open up their facilities so people can reply online.”

The Trump administration’s attempt to add a citizenship question to the Census has also made many non-citizens, and citizens with undocumented relatives, wary of this year’s Census. Following a decision from the U.S. Supreme Court, the proposed question was struck down and the 2020 form does not ask for citizenship status. Instead, the administration is seeking to build a citizenship list from other data sources. But confusion over the topic and fear in the immigrant community is likely to deter participation and lead to an undercount, former Census administrator Mark Doms told Reveal.

One way to spread the word in hard-to-reach communities is to make sure that the Census workers who will go door-to-door are actually from the community, according to Maddaloni. “That’s why it’s so important we have a large applicant pool from these hard-to-count areas,” he says.

These temporary Census jobs pay from around $13.50 an hour to more than $20 an hour, depending on locality, and have flexible hours, according to Maddaloni, who encouraged interested job-seekers to apply at 2020census.gov/jobs. Applicants have to go through a formal background check and will receive training.

“It could be a second job for some,” says Maddaloni. “We need more people to apply to make sure we can get an accurate count.”

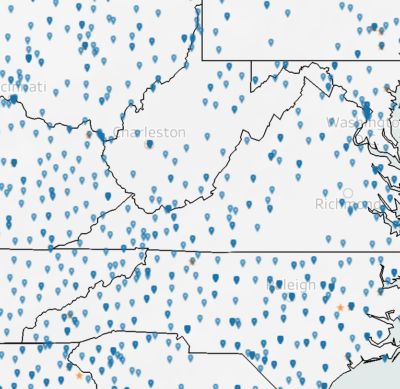

Complete Count Committees aim to make sure an area is fully counted. Map of Census Count Committees, accessed from U.S. Census Bureau website, Feb. 4, 2020.

These committees are part of a Census program designed to help states and localities educate and encourage residents to take part in the Census. Committees are made up of local government and community leaders. They receive Census training and can direct local funding to increase awareness of the Census.

“A little bit of state funding can have a huge return on investment,” says Allen. “This will help make sure we get our fair share of federal funding — which is so important in these areas that have been historically underinvested in.”

Census data can be extraordinarily valuable for local communities, according to Zimmerman.

“One of the things the Census can do is give us local information so that we can plan for our futures,” she says. “This is of particular importance in Appalachia as we are facing a post-coal transition. Knowing what these numbers are is even more essential.”

Census data helps communities know when they need to build new schools, plan road construction, adjust zoning regulations, set public transportation routes and adapt other services, according to Allen.

“It’s not just another bureaucratic form,” she says. “The data help us see how families are doing. It definitely helps us identify opportunities for better policies and what areas need more help.”

The data can also be put to more personal use, according to Zimmerman. She states that families have used Census information to trace their family histories. Importantly, she adds, the law requires that personal information collected during the Census stay hidden for 72 years.

“The Census is totally confidential, says Zimmerman. “Census employees take a lifetime oath.”

What the Census counts: The goal of the Census is to count every resident living in a particular place on April 1, 2020. That includes non-citizens, children under 5, relatives sleeping on a couch, students living in a dorm, and people living in jail cells or on the street. Visitors should be counted in the place where they live and sleep most of the time. If they don’t have a normal residence to return to, they should be counted where they are on April 1.

What the Census counts: The goal of the Census is to count every resident living in a particular place on April 1, 2020. That includes non-citizens, children under 5, relatives sleeping on a couch, students living in a dorm, and people living in jail cells or on the street. Visitors should be counted in the place where they live and sleep most of the time. If they don’t have a normal residence to return to, they should be counted where they are on April 1.

What to expect: Most households will receive a postcard in mid-March that includes a URL and a unique code to respond online. Residents will also be able to call a toll-free number to complete their census. Some households in hard-to-count areas will receive a hand-delivered door-hanger. Following that initial contact, reminders will go out weekly. The fourth reminder will include a paper questionnaire. Around the end of April, after the fifth reminder, Census workers will start going door-to-door to households that haven’t responded.

How to contact the Census:The answers to many questions can be found at 2020census.gov. Information about temporary Census jobs and how much they pay can be found at 2020census.gov/jobs. The Philadelphia office, which covers most of Northern and Central Appalachia, can be reached at (800) 262-4263. The Atlanta office, covering Southern Appalachia, can be reached at (800) 424-6974.

What Census workers won’t ask: No one from the Census will ask you for your citizenship status, Social Security number, credit card or bank information or donations. Every Census worker has an ID badge. To verify whether someone actually works for the Census, call (800) 923-8282.

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests