From left to right: a basically normal human lung; a lung with coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, also known as black lung disease; a lung with coal workers’ pneumoconiosis and progressive massive fibrosis, also known as severe black lung disease. Photos courtesy of CDC-NIOSH

“Those of us with bad lungs, we’re all just staying home now. If we come into contact with coronavirus, it would just destroy our lungs,” said Arvin Hanshaw, a former miner and the president of the Nicholas County WV Black Lung Association, an organization of miners with black lung and their friends and family. “We’ve suspended our meetings until this all blows over. School is cancelled. Churches aren’t congregating. Most everything is shut down.”

Hanshaw and other current and former miners depend on black lung clinics for diagnostics, rehabilitation services and assistance with the arduous process of filing a claim for medical coverage and disability benefits through the U.S. Department of Labor. As the coronavirus pandemic spreads, these clinics are trying to strike a balance between providing medical services and adhering to heightened safety protocols.

“I’ve been going to rehab [at New River Health’s black lung clinic in Scarbro, W.Va.,] for six or eight weeks now, and it’s done wonders for me,” says Hanshaw. “But they’ve had to shut it down now until further notice.”

Healthcare Providers Respond

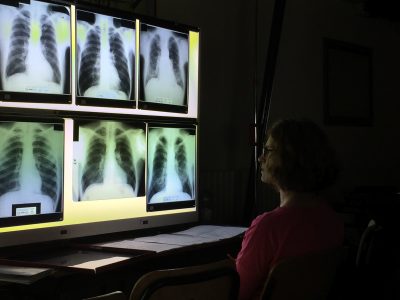

A participant in a federal course geared toward spotting black lung symptoms evaluates various chest x-rays. Photo courtesy of CDC-NIOSH

“During this pandemic, we must concentrate on stopping the spread,” says Wills. “We are not filing new claims right now. Some miners will become ill and we have to see those folks, or, in some cases, get them to hospitals. But we are trying to keep the spread at a minimum.”

Some of the protocols Valley Health had in place as of March 23 include scheduling well patients in the mornings and sick patients in the afternoons, asking patients with temperatures and respiratory symptoms to call ahead, screening everyone for possible coronavirus symptoms at the door, and having potentially infected patients enter through a fire escape into a specially designated examination room.

In order to reduce the risk of exposure for patients and staff, the Carson Black Lung Center in Pineville, Ky., has begun conducting benefits counseling over the phone whenever possible and has canceled all depositions involved in the claims process until further notice. As of March 23, in-person diagnostic services were continuing with all surfaces and exam rooms thoroughly cleaned between each patient, but only after clinic staff had discussed potential coronavirus symptoms with the miner over the phone, allowing each party an opportunity to reschedule the appointment.

“Safety is the number-one priority,” says Cindy Viers, director of the Carson Black Lung Center. “With the lungs already compromised, this could be a death sentence.”

Retired miners with black lung wore shirts with this design during a July lobbying trip to D.C. The Black Lung Association has used the image for decades.

“Our guys decondition rapidly,” says Marcy Tate, director of New Beginnings Pulmonary Rehab, which serves miners at two locations in Southwestern Virginia and one in Eastern Kentucky. “We know if these guys stop doing rehab, they lose ground rapidly. If we have to close for even two weeks, I don’t know how many would make it back to us.”

Pulmonary rehabilitation consists of exercises designed to strengthen the diaphragm, thoracic muscles and lungs, and to teach patients how to exercise without over-exerting. New Beginnings and other rehabilitation centers provide patients with printed instructions for doing exercises at home, but Tate and other healthcare providers feel that these may not be as effective as the rehab that is possible in a clinic setting with exercise equipment and staff on hand. Additionally, the social atmosphere of rehabilitation centers provides an excellent motivator that can’t be accounted for in individual in-home workouts.

New Beginnings’ Kentucky location closed down on March 20 after Gov. Andy Beshear ordered the closure of non-essential business in the state. But Tate says they will maintain services at their Virginia locations for as long as they are able to do so in compliance with federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidances, and other government directives.

“Our equipment is spaced more than six feet apart. We sanitize every machine between every miner. We screen them for symptoms at the door. If anyone has a fever or anything, we’ll send them straight to the [Wise County] Health Department, and then sanitize the entryway.”

Miners and Industry at Odds Over Funding for Care and Benefits

Living with black lung was already perilous, and the threat of the coronavirus has compounded that peril for thousands of miners. Adding insult to injury, coal industry lobbyists are now trying to take advantage of the COVID-19 crisis at the expense of black lung patients. On March 18, the National Mining Association sent a letter to President Donald Trump and congressional leaders asking for a 50 percent reduction in an excise tax on coal companies that funds healthcare and benefits for some 25,000 miners with black lung.

Congress already allowed the excise tax to be halved in January 2019. Although legislators restored the tax to its original level in December, it will be halved again in 2021 if Congress fails to act. The Black Lung Association continues to call for a 10-year extension of the tax.

Tell your representative to stand up for coal miners and extend the excise tax by at least 10 years!

“They’re just trying to get out of paying what they owe to the people that worked for them,” says Arvin Hanshaw. “This coronavirus is just a disease that’s come upon us, and it has no bearing on the black lung excise tax at all.”

Even before the National Mining Association letter, the Black Lung Association had been pushing for a 10-year extension to the excise tax. Despite the cancellation of meetings and other social distancing measures undertaken in response to COVID-19, miners and healthcare providers alike intend to continue advocating for this crucial funding source for black lung benefits and care.

“I don’t know how just yet, with us not meeting, but we’ll keep working on it,” says Hanshaw.

“Just because we’re not meeting, doesn’t we mean we can’t still be active,” says Cindy Viers of the Carson Black Lung Center. “This too shall pass, and we’re still gonna have to fight for our miners.”

Leave a Reply