Contributing Writers | November 2, 2020 | No Comments

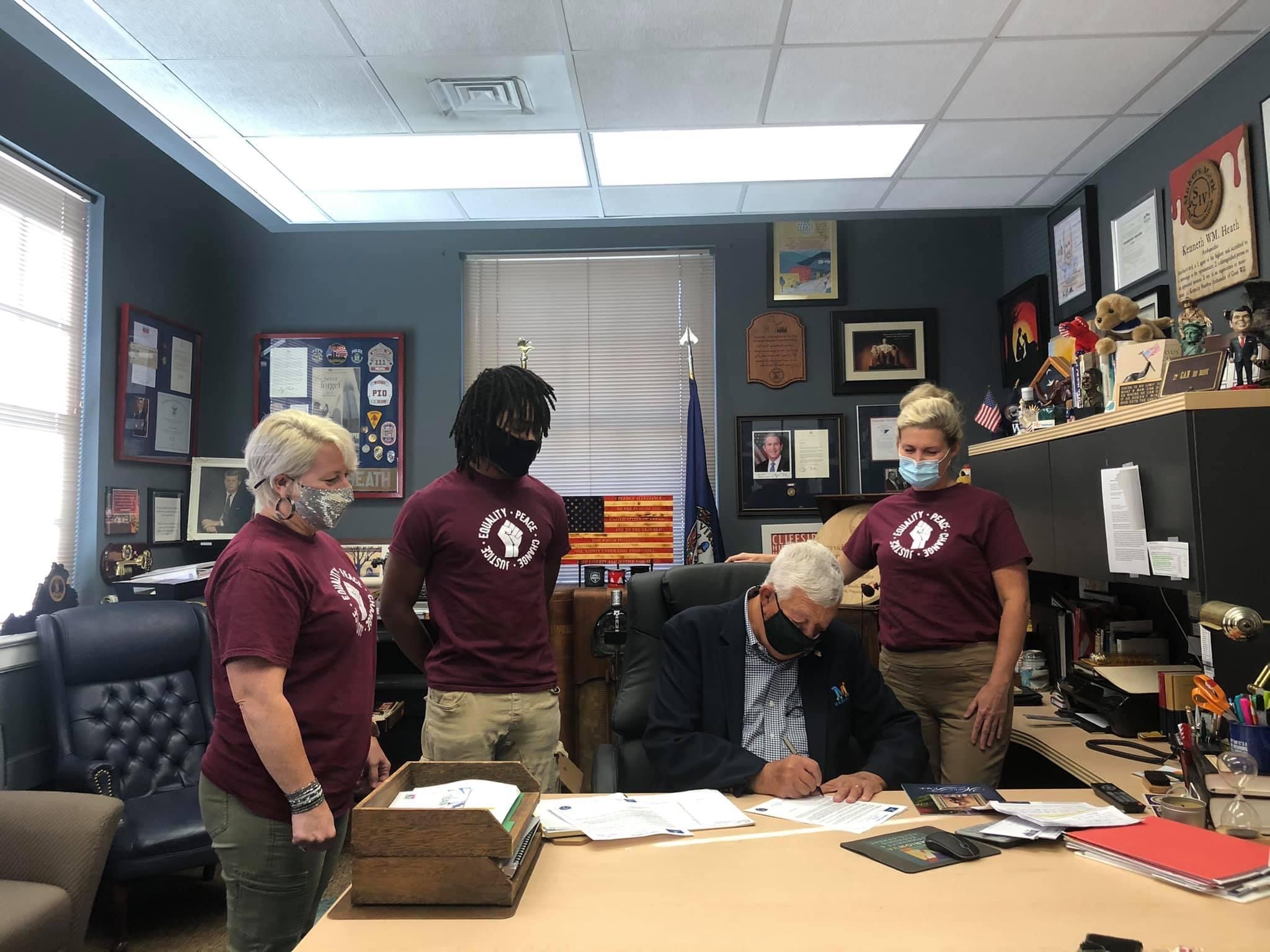

From left to right, Sabrina Meadows, Travon Brown and Misty Russell of Justice, Equality, Peace, Change look on as Marion Mayor David Helms signs a resolution denouncing racism and discrimination on Oct. 19, 2020. Photo courtesy of JEPC

By Alexis Wray

The town of Marion, Virginia, recently denounced racism after social and criminal justice reform group Justice, Equality, Peace, Change worked with town officials to draft a declaration that combats racism, sexism, xenophobia and discrimination.

On Oct. 19, the JEPC-sponsored resolution made Marion the first town in Southwest Virginia to formally denounce racism. The declaration expressed, “the Council of the Town of Marion condemns events of racism, discrimination, and inequality that exist in our community, our nation, and world.”

The Bristol, Virginia, city council unanimously approved a similar resolution Oct. 27. The resolution was supported by JEPC and a local group called Community Concerned Citizens, according to local news reports.

“There can be no community without working towards the goal of UNITY!” Travon Brown, the 17-year-old chair of JEPC said in a statement. “Let’s come together to combat racism & discrimination out of our communities in [Southwest Virginia] and beyond. We don’t expect to change everyone, but we will do what is needed to ensure the next generation can live better lives.”

Leaders like Brown are driving the movement forward and seeking social justice in their communities. Organizations built to fight for equity and uplift Black lives are surging throughout the Appalachian Mountains and young leaders are steering the way.

Some existing and other newly formed groups are amplifying their focuses after the brutal killing of George Floyd by police officer Derek Chauvin in May in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Chauvin applied extreme force and compression to the back of Floyd’s neck during an arrest. The global impact of Floyd’s death sparked action among passionate community members seeking justice nationally and locally for Black lives.

Actions of the movement are carried out as a result of constant injustice and inequality that Black individuals have experienced in the United States for more than 400 years. Youth-led groups like JEPC and the regional youth network built to encourage Black youth leadership, Black Appalachian Young and Rising, are committed to shedding light on and uplifting Black communities.

In the midst of a global pandemic and heightened social awareness, Americans have been forced to see the injustice that affects Black lives on a daily basis. According to vice chair of JEPC and White ally Misty Russell, this summer she saw the country at a moment of pause with no distractions from the injustice.

“That was a pivotal moment for people to ask themselves, ‘is this okay?’” says Russell. “This is a door for people to make a change. The line was drawn and enough is enough.”

The Appalachian region is significantly less racially and ethnically diverse than the United States as a whole, according to the nonprofit research organization Population Reference Bureau. Black communities in Appalachia are not only faced with the typical barriers of a rural lifestyle, including remote location, few career opportunities and lack of transportation, they also face racism, microaggressions, white privilege, hate signs and discrimination. A common community sentiment remains that these obstacles make it near to impossible for many Black individuals to thrive in rural areas.

Mekyah Davis, a young Black leader in the region, is trying to change that. Davis is the coordinator of Black Appalachian Young and Rising and co-coordinator of the STAY Project, a network of young people who, as their website states, aim “to make Appalachia a place we can and want to stay.” He works to build an Appalachia where young, diverse leaders can create inclusive communities, and he describes BAYR as a “collective of young Black folks coming together throughout the Appalachian region overcoming fiscal and physiological isolation.”

In 2019, during Black Appalachian Young and Rising’s first gathering, Black youth throughout the Appalachian region came together at Pine Mountain Settlement School in Eastern Kentucky to address the lack of young Black leadership in movement spaces. From left to right, Anya Badger, Nina Morgan, Sydney Underwood, Ge’onoah Davis, Trey Lomax and Mekyah Davis. Photo courtesy of BAYR

Davis grew up in Big Stone Gap, Virginia, a traditionally coal-reliant area that has an African American population of 19.2 percent and a White population of 79.1 percent, according to 2019 U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

Big Stone Gap is known as the “Mineral City” and served as a key developer for coal and iron. This industry attracted economically disadvantaged men that wanted to build a better life for their families, and it provided unskilled workers with jobs. A lot of the unskilled workers were Black men who played an important part in the labor force of the coal industry.

Reverend Sandra Jones, pastor of Williams Chapel AME Zion Church, grew up in Big Stone Gap before integration.

“People migrated from here when the coal mine shut down,” Jones recalls. “A lot of the people left, especially the Black population because that was their livelihood.”

While rural areas like Big Stone Gap used to have more job opportunities in the coal industry, they also used to have a larger population of Black individuals compared to current census reports.

“My mom said all she knew growing up was Black folks,” says Davis. “The neighborhood was full of Black kids, but my experience growing up was very much surrounded by White people. The young Black folks who were around were family or neighbors.”

Davis’ passion for combating racial injustice in Appalachia stems from a lack of Black youth leadership. Black Appalachian Young and Rising works regionally through Southwest Virginia, Eastern Kentucky, Western North Carolina and other Appalachian regions to empower young Black leaders. He believes in discussing and examining how the group can address the critical lack of Black youth leadership in social justice movement spaces.

As a founding member of BAYR, Davis works to create spaces for Black Appalachian youth to identify their joy and thrive regardless of experiences and systems of racism or injustice. The STAY Project is focused on doing what it takes to uplift and appoint Black youth leadership and has supported and motivated Davis to, as he says, bring Black Appalachian youth together to “develop a collective political analysis by being in commune with one another.”

In Southwest Virginia, 150 people turned out for a vigil on June 7 in honor of Black people killed by police brutality in America. The event was organized by local Black youth and included a march in Big Stone Gap, songs, and a listening circle where Black community members were invited to share their stories of experiencing racism and call on white people to be anti-racist, call out racism and talk to other white people about racism. Photo by Willie Dodson

“When they had our march in Big Stone Gap, I saw our future there, I saw the ones that were really going to make some changes in this area,” says Jones, the Williams Chapel AME Zion Church pastor. “I was absolutely pleased with that group of young people.”

More than 150 people gathered and marched to the vigil out of respect for Floyd. Various Black community members shared their experiences, along with uplifting words of perseverance. According to Jones, this historic day in Big Stone Gap brought broader awareness to years of racist community experiences and encouraged unity and change.

“Bringing our community together to unify is going to take young people,” she says. “I have played my part and now it is their part. All I want to do is support them in any way that I can.”

With the support of community pillars, young Black leaders are continuing to emerge in Appalachia, including Travon Brown, chair of Justice, Equality, Peace, Change. Brown is a high school senior, track star and activist for Black lives and unity in Marion, Virginia.

Brown started organizing because he wanted to help and defend his community by combating racism. When protests kicked off across the country in large cities like Minneapolis, Portland, Louisville and Atlanta, Brown traveled to march and be a part of the movement. He first attended a protest in Johnson City, Tennessee, led by the New Panthers Initiative, a social activist group fighting for change in the Black community.

During Community Resource Day in September, members of Justice Equality Peace Change passed out nonperishable food items and toiletries to people in the community in downtown Marion, Virginia. Photo courtesy of JEPC

JEPC is managed by a small team of dedicated allies looking to support Brown and ensure change for African Americans, people of color, women, children and all oppressed groups to have equality, justice and peace.

“One of our goals is to be a voice and representation for anyone who has been discriminated against, oppressed, or has an issue that we can guide them through,” says JEPC Vice Chair Misty Russell. “The change is going to come as long as people keep speaking out.”

The organization seeks to provide assistance to those who need a voice, but they started supporting the African American community of Marion first, which the U.S. Census Bureau reports as 9.6 percent.

“Life, liberty and justice,” says Brown. “Black people are still fighting for our lives. We don’t have liberty. We don’t have justice.”

Following Brown’s first march in Marion on June 13, this rural Southern Appalachian town circulated through national news networks because of the threat-filled crime of a cross-burning in Brown’s yard. The cross was burned in his yard as an attempt to scare and deter Brown from organizing future protest.

James Brown, a 40-year-old White man who lives directly across the street from Travon Brown, was charged with two federal crimes for dousing a wooden cross with flame propellant and setting it on fire on Travon Brown’s family’s property.

After the crime, Travon Brown released a statement saying, “I believe it was a scaring tactic but nevertheless it has failed. I am planning more things for our community and can’t wait to see what tomorrow holds.”

The hate was met with Brown’s resilience and motivation. A few weeks later, he proceeded to organize another march. Brown continues to demand justice for his community.

“‘Injustice anywhere is affecting justice everywhere,’ I strongly go by and live by that quote,” he says, referring to a quote by Martin Luther King, Jr.

Organizing in rural Appalachia for Black lives is vulnerable work that is met with risk, fears and constant uncertainty of safety. Although the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution permits the people to peaceably assemble, Black Americans have faced constant brutality and inhumanity while exercising their rights.

“We go off of the understanding that our country is not only built on slavery but also on anti-Black sentiment,” says Davis. “If we start at that, we can understand why the law and everything else is meant to reflect that anti-Black sentiment and to protect the ruling class.”

Regardless of the inequity and injustice, Brown and Davis continue to combat the issues that affect their communities.

After working with the town to denounce racism in Marion, JEPC also sought to rectify the racist experiences of Black individuals in Bristol, Virginia, through the passage of a resolution denouncing racism on October 27.

Bristol, Virginia, adopted a resolution to denounce racism and discrimination on Oct. 27. Photo courtesy of JEPC

BAYR’s website proposes that “state violence and erasures amongst systems of racism and economic injustice” continue to intersect with the existence and growth of Black youth in Appalachia. They seek to guide the restorative process for Black youth to stay and thrive in the Appalachian Mountains.

Davis explains that “the structures of white supremacy affect White people in rural areas too.”

“I think about the legacy of extractive industries… about environmental racism, how poor folks or Black folks are more likely to face the brunt of environmental racism and the legacies of extractive industries,” he continues.

As the movement for Black lives expands, these young Black leaders continue to advance their regions by overcoming the odds and aiming for victories that push the movement forward.

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests