Contributing Writers | June 2, 2022 | No Comments

The University of North Georgia Appalachian Studies Center’s signature project, the Saving Appalachian Gardens and Stories, is a demonstration garden for heirloom seeds and an oral history collection. Photo courtesy Rosann Kent.

Chelsea Askew, a farmer from Northwestern Georgia, grows many fruits and grains. By fostering a hospitable environment for their seeds to recreate, she can then collect those seeds, saving them for the next year.

“Seeds contain all the DNA and essential first energy sources for that seed to become a plant,” Askew says. “All of that’s packaged in there — whether a tomato or corn kernel. It allows you to continue to grow that particular kind of plant. More of my focus is to continue to select the [seeds] that do well in the area where I grow them and that are adapting to the changes in the climate and things like that — selecting for resiliency.”

Example of variation or genetic diversity in cob color of Bryant corn. Photo by William Ritter.

Seed saving and the communities that form around the practice allow gardeners and farmers to explore new varieties of the plants they grow that may not be available in stores and garden centers. Saving seeds preserves food culture and allows farmers and gardeners to pass heirloom seeds to future generations. This practice allows gardeners and farmers to connect with others through common interest, explore the genetic diversity of plants and increase their capacity as a grower.

“There are all these different beans in Appalachia, but it becomes its own bean in its own holler,” Askew says. “It’s formed by that particular angle of the sun in that holler, the soil there, the rocks that are weathered down, and the person, family and generations that have continued to select for what they’ve wanted to eat and continued to eat. It’s constantly evolving and has the potential to be ever more nutritious and resilient.”

The 1970 Plant Variety Protection Act, which grants plant breeders intellectual property rights protection, was one factor that made seed saving more difficult for farmers and breeders. In many cases, small farmers are not able to save seeds or use patented seeds to breed new varieties. Four seed companies control more than 50% of global seed sales. This market concentration drives prices higher, limits seed availability, variety and adaptability, and provides growers with seeds that lack historical relevance.

Seed saving supplies stored in a cool space away from direct light. Photo courtesy of Rosann Kent.

Hybridization is the process of interbreeding genetically distinct plant populations to produce a hybrid. Saving seeds from a hybridized plant is unpredictable and will not yield the same plant the next year, and in many cases, no plant will grow from the saved seeds at all.

Not having to purchase seeds every year saves growers money and diverts dollars away from large corporations. With some simple tools and a little time, seed saving can save money. Resources like seed swaps, an event for growers to exchange seeds, and seed libraries, a place where people “borrow” seeds at the beginning of growing season and return saved seeds at the end of the season, give local growers seeds at a lower cost than retail corporations.

According to Askew, seed saving is a way to ensure seed availability and decrease growers’ reliance on large corporations and inconsistent supply chains.

“A big thing to me is the self-sufficiency thing,” she says. “Growing what I want and not having to rely on a corporation to be able to grow the food to nourish me and my community and being able to select … for stuff that does well in this area — most of what I grow has been grown here for quite some time. It feels satisfying to be connected in that way. Soil and climate and animals come together to produce amazing flavor and resiliency.”

Seed saving has ecological benefits as well as financial — particularly in the face of changing climates.

Lyndsey Butterbeans saved in Avery County, NC. Photo by William Ritter.

Askew describes that seeds with their own rich built-in genetics, like heirlooms, are more adept to react to climate changes.

“Selecting for resiliency means self-sufficiency as well, not dependent on outside sources or corporations for your food if you can create a hospitable enough environment,” Askew adds.

Seed saving provides opportunity for community connections through seed swaps and other events.

These connections benefit breeders.

“Seed saving and communities shine by getting to meet other people who [seed save] in your community and sharing with them,” Askew says. “Sharing increases diversity, and oftentimes, there are varieties that are happy to be grown in that area. For folks who want to get started, there’s a lot of information to be gathered from those sorts of exchanges.”

”It’s a deeper connection to hear about the beans or corn that’s been grown in that family for a long time,” she says.

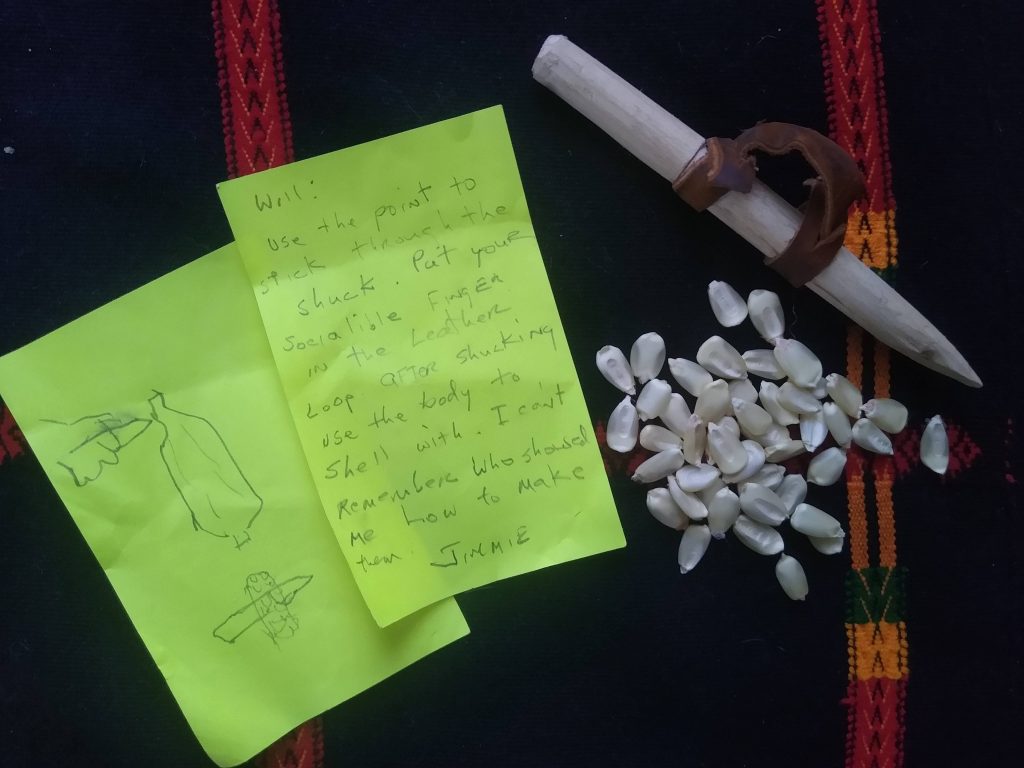

Corn sheller/shucker with instructions from seed-saver Jimmy Bryant in Caldwell County, NC. Photo by William Ritter.

Some families are able to keep seed varieties around for decades. Seeds that have been bred for a specific valley give a community an opportunity for self reliance — a cultural tradition for many Appalachian families. The culture of independence is alive and well in the region, and seed saving plays a role in this resilience.

“We know that in southern Appalachia, people who are still growing with their families and their seeds hold this information,” says Rosann Kent, the director of the Appalachian Studies Center at the University of North Georgia. ”We save heirloom seeds that have never been bought or sold and that are passed down from family-to-family or communities pre-1950.”

The University of North Georgia Appalachian Studies Center’s signature project, the Saving Appalachian Gardens and Stories, is a demonstration garden for heirloom seeds and an oral history collection. The garden shows visitors how regenerative agriculture works and is designed to help people share seeds with neighbors. Project participants preserve cultural history through interviews with seed donors about their gardening traditions and practices of Southern Appalachia. Kent oversees the Appalachian Studies Center’s story collection.

“There are so many Appalachian students who don’t know what treasures their family has,” she says. “As an Appalachian Studies Center, that [story collection] helps us keep what is good about Appalachia alive.”

Seed saving reconnects communities with the land, William Ritter, a musician and farmer from Western North Carolina, explains.

William Ritter giving a song to seed presentation in Maggie Valley, NC. Photo by Wayne Ebinger.

“If everyone’s just buying [seeds], I think [growers] are missing out on something,” he says. “I think as a collective we’re missing out on the diversity and people having a rich cross-cultural experience where they get to make connections where maybe they’re very politically divided, but they can share their mutual love for greasy beans. You can take a stake in your community by committing to something from that community and it changes your relationship with that place.”

Places like seed swaps provide an opportunity for connecting with the community and land.

“The big part of why I got into seed saving is because I wanted to have a personal connection to the seeds that had a face behind them,” Ritter continues. “Seeds are really rooted in place and become specialized to that garden and that area. I wanted to get into seed saving not to have a big freezer full, but to have connections to those gardens and places.”

Connections made at seed swaps are helpful not only in terms of knowledge but also for culture and heritage, Ritter explains. Exchanging seeds and knowledge can give a beginning farmer some much-needed first-hand connection with people in the community that have the same interests and have been stewarding and nurturing for generations.

While the idea of long-term genetic breeding and selection may seem overwhelming, seed saving is possible for anyone. Gardeners should select from plants that have thrived and are healthy enough at the end of the season to produce seeds so that the next year, they will have plants that are better adapted to their conditions.

When starting a garden in the spring, gardeners should learn if the plants they intend to grow are hybrid or open-pollinated varieties, and understand how the plants pollinate to prevent cross-pollination. Isolation distance refers to plants’ required distance apart to prevent cross-pollination.

When selecting seeds, growers should choose healthy plants and try to observe the parent plants throughout the season. Beginners can start with plants that produce seed the same season they are planted, such as tomatoes, peppers, and beans to keep things simple.

Seed Saver John Leopard saves Hamburg corn from Jackson County, NC. Photo by William Ritter.

Growers should try to harvest the seed after it has matured but before it falls off the plant. Do not simply save the last seeds of the season for risk of selecting for a late-growing characteristic or gathering only seeds that might be poorer in quality than a seed matured in the middle of the harvest period. Seeds should be stored in a cool, dry location — refrigerators are ideal.

“Tomatoes are pretty accessible as far as seed saving because there’s not a huge isolation distance required to keep things pure,” Askew recommends. “Even if you start with a couple varieties, it is much easier to just focus on understanding a couple different varieties and what that involves.”

Seed saving is an opportunity for growers to be in tune with the health of their plants, become more self-reliant, and connect with the land and community.

Askew says, “I found it very empowering to have and grow my own seeds and select traits that I value — which are primarily flavor and resiliency.”

Seed Savers Exchange: https://www.seedsavers.org/

Carolina Farm Stewardship Association: https://www.carolinafarmstewards.org/seed-production-guides/

Gary Nabhan (website and any of his books)

Your local public library may have a seed library and books about gardening!

Dave Walker contributed to this article.

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests