Contributing Writers | November 23, 2022 | No Comments

By Maggie Allan

With inflation rising, every dollar that a miner with black lung disease receives as part of their disability benefits has less purchasing power. But if a bill currently before Congress passes, people with the debilitating disease would see a small increase in their monthly benefits, and the level of benefits would be tied to inflation.

That change is one of many included in the Black Lung Benefits Improvement Act. A recent report by Democratic staff of the House Education and Labor Committee describes the legislation as “a set of reforms to put miners and their survivors on a more equal footing with coal operators.”

In 1972, Congress established a system for miners to file a claim for benefits if they are disabled by black lung, a deadly disease caused by exposure to coal dust.. The benefits system has provided a lifeline to thousands of miners in need, but the process has been slow and confusing, and it has tended to favor coal companies over miners. In addition to adjusting black lung benefit levels, the current bill would improve access to benefits and payment of medical expenses for miners with black lung.

The Black Lung Benefits Improvement Act advanced out of its U.S. House of Representatives committee on party lines this spring, with the Democrats in support and the Republicans opposed. A Senate version was referred to committee in July, but the legislation faces uncertain odds in a sharply divided Congress.

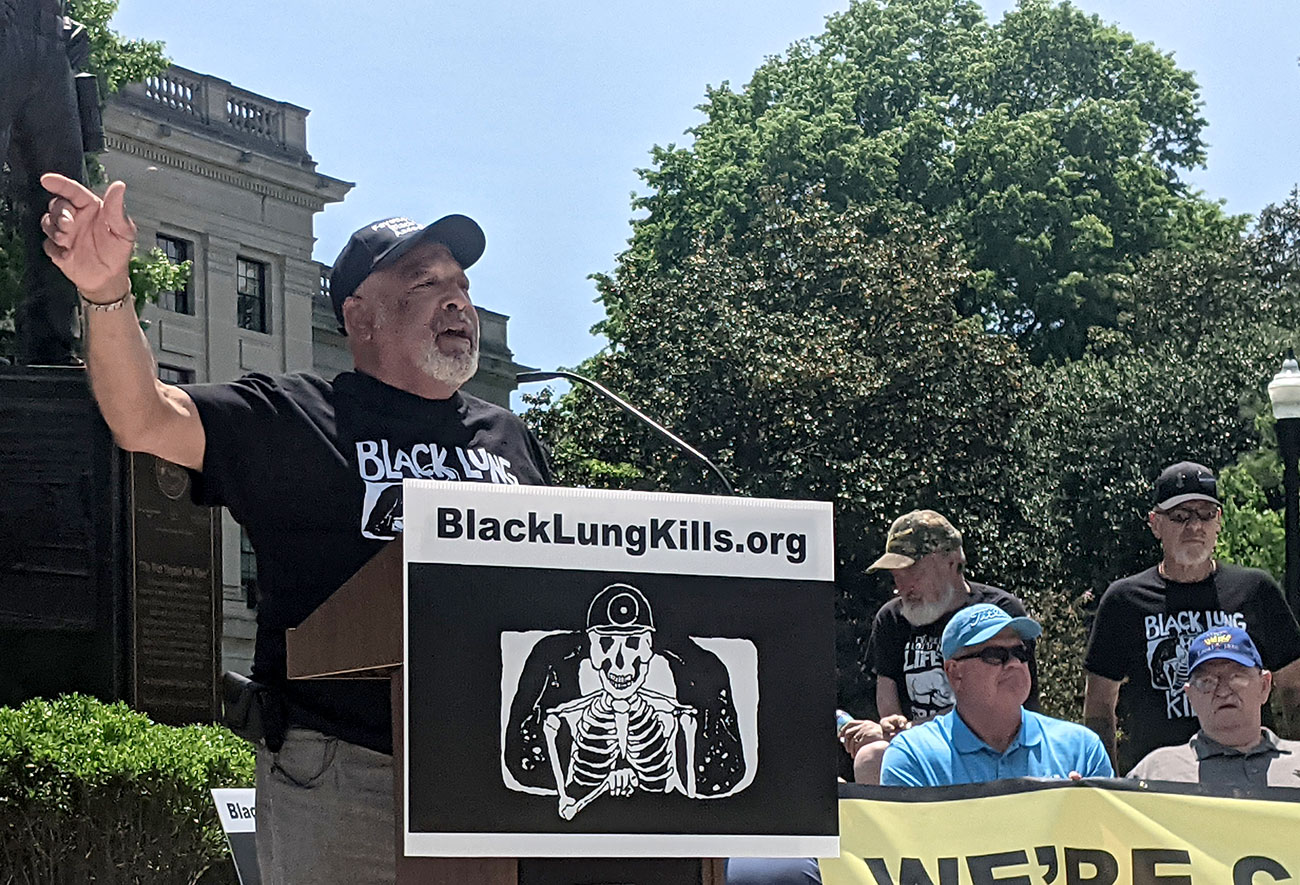

Gary Hairston, president of the National Black Lung Association, speaks at a May 2022 press conference in Charleston, West Virginia. The press conference was part of a successful campaign to ensure that funding for black lung benefits would be included in the 2022 budget reconciliation bill.

Under current law, coal miners who are disabled with black lung are legally entitled to monetary benefits, as well as medical care related to the disease. While the medical expenses often rise to thousands of dollars each month, the benefit payments are modest. Each miner currently gets $709 per month, plus more for each dependent. The full $709 amount is paid out to the widow of any miner who has passed away as a result of the disease. But accessing these benefits and medical payments is not a simple matter.

“It takes a miner on average seven years to settle a federal black lung claim,” says Debbie Wills, black lung program coordinator at Valley Health Systems in Cedar Grove, West Virginia. “When a miner files a claim, and it takes 18, 19, 20 months to get an initial decision, that’s a pretty long time for them,” Wills explains. “In the meantime, the disease isn’t getting any better.”

The process is not only slow, but cumbersome. “In a federal black lung claim, a miner has to prove that he is 100% disabled by a respiratory problem from his regular coal mine job,” Wills says. This requires a diagnosis by a federally approved doctor, and the submission of various paperwork verifying details of the miner’s employment and medical history.

The process is also expensive, causing many black lung claimants to become overwhelmed by legal fees and healthcare costs, with some miners giving up before ever filing a claim.

If a miner makes it through the process and their claim is approved, the monthly benefits and the miner’s medical care should be provided by the last company that employed the miner for at least 12 months. But if that company is unable to pay – an increasingly common scenario amidst an ongoing trend of coal company bankruptcies – the benefits and medical expenses are paid out of the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund.

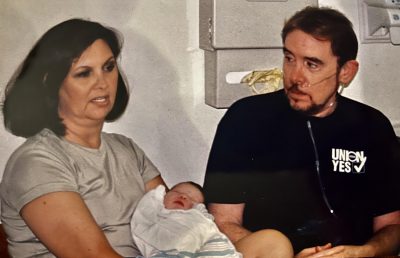

Kathryn and Mike South fought through this process, facing many of the problems embedded in the system. For decades, Kathryn endured the arduous legal process to obtain federal black lung benefits, first for her husband, and then for herself as a miner’s widow after her husband’s eventual death from the disease.

A portion of the equipment coal miners must wear daily is shown in the painting “Gear” by Mike South.

So Mike and Kathryn found a lawyer and got to work filing their claim. Kathryn explains that because Mike’s lung function was so low at such a young age, his black lung claim was easier to prove than it often is for older miners, or for miners whose affliction, though significant, may not rise to the 100% disability threshold.

“We didn’t have to wait as long as most people to actually get the benefits,” she says.

Still, Mike’s claim took about six years to process. Meanwhile, social security payments and Kathryn’s paycheck got the family of four through.

On July 19, 2001, Mike passed away in the ICU at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

After his death, Mike’s medical expenses left Kathryn with an unthinkable financial burden.

An amendment to the Black Lung Benefits Act that passed in 2010 certifies that any widow of a benefits-receiving miner is automatically entitled to widows’ benefits after her husband’s death. But because her husband died before this amendment, Kathryn again had to fight through the claims process to retain the $700 per month payment that she relied on while her husband was alive.

Mike South and Kathryn South holding their granddaughter Jadah South in 1998. Photo courtesy of the South family.

Throughout all this, Mike and Kathryn worked to help others in a similar situation. They both became respected leaders within the black lung movement, with Mike serving as the president of the National Black Lung Association during the 1990s. Now, more than two decades after Mike passed away from the disease, miners with black lung are still having to wade through a lengthy and confusing claims process, and the Black Lung Association is still there to help them. Kathryn shares their story to help improve the policies that stood in their way.

Informed by decades of firsthand stories like that of Kathryn and Mike South, Rep. Bobby Scott (D-Va.) and other miners’ allies in Washington crafted the Black Lung Benefits Improvement Act with an aim to improve the claims process for miners and their dependents from start to finish.

“There is a lot of good stuff packed into the bill,” says Chelsea Barnes, legislative director for Appalachian Voices, the organization that publishes The Appalachian Voice. According to Barnes, the bill “makes clarifications to help doctors diagnose the disease, and helps miners prove their diagnosis.”

Historically, confusion around diagnostic criteria – especially for progressive massive fibrosis, the most severe form of black lung disease – has skewed the process in favor of coal companies seeking to avoid paying for miners’ benefits and medical expenses.

“The bill also creates a payment system to encourage more attorneys to take on black lung cases, by making sure the attorneys can receive partial payment earlier in the claims process,” Barnes says. Currently, payment isn’t issued until the conclusion of the often years-long appeals process – a setup that disincentivizes lawyers from taking on black lung cases.

Another provision in the bill seeks to level the legal playing field by subjecting coal companies to penalties for making false claims. Currently, such penalties only apply to claimants such as miners and widows.

For miners receiving benefits, the Black Lung Benefits Improvement Act would provide a small increase in the monthly benefit amount, and it would tie that figure to inflation moving forward.

Building on the recent permanent extension of the black lung excise tax, the Black Lung Benefits Improvement Act would further alleviate financial strain on the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund by requiring the Department of Labor to tighten rules around the way coal companies are currently able to self-insure. This is when a company relies on its own financial reserves to deal with unforeseen losses, instead of purchasing a third-party insurance policy for that purpose. In recent years, some self-insured companies have proven unable to honor their black lung obligations, forcing the trust fund to pick up the tab.

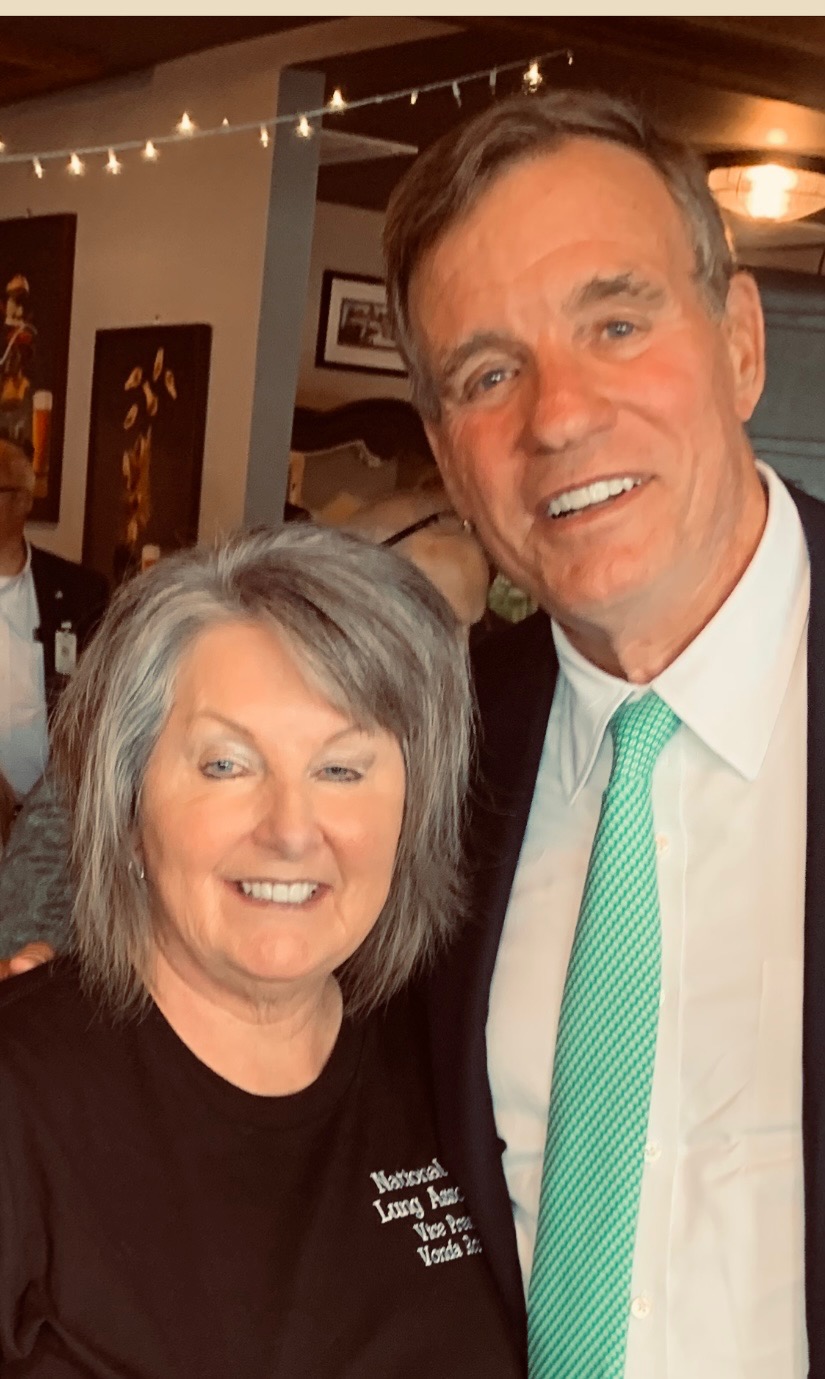

Another bill aimed specifically at making it easier for widows and other dependents of miners who died from black lung to receive benefits was introduced by Senator Warner (D-Va.) in 2021. The Relief for Survivors of Miners Act, nicknamed the Widows’ Bill, was introduced after multiple discussions between Warner, miners and miners’ family members from his home state.

The Widows’ Bill would establish in law that black lung is presumed to be the cause of death whenever a miner with black lung dies. This would automatically entitle the miner’s widow to monthly benefits. Currently, in order to draw these benefits, bereaved widows have to prove that black lung caused the death, which in some cases includes having an autopsy performed on their deceased spouses.

Under the system proposed in the Widows’ Bill, the miner’s previous employer would have a right to challenge this presumption, and the final cause of death would ultimately be determined in an administrative legal proceeding. If passed, the legislation would shift the burden of proof from the miner’s family to the coal company for which the miner worked.

Vonda Robinson, vice president of the National Black Lung Association, meets with Virginia Sen. Mark Warner in August 2022. Photo courtesy of Vonda Robinson

“He took his jacket off, loosened his tie, and walked from table to table at the meetup asking the women, ‘let me hear your story,’” Robinson says.

This meeting was a key part of the push for what eventually became the Widows’ Bill, and it further solidified an ongoing dialogue between the senator and families who are impacted by black lung.

“After everything miners have done to power our nation, it’s only right that their families are able to access the benefits they deserve – that’s why I’ve been proud to champion the Relief for Survivors of Miners Act and the Black Lung Benefits Improvement Act,” said Warner in a statement provided to Appalachian Voices. “These two pieces of legislation will eliminate bureaucratic hurdles that make it difficult for widows and surviving families to claim the benefits they deserve, while allowing miners suffering from black lung to more easily access the medical and legal resources they need.”

“Unfortunately neither of these bills have the bipartisan support necessary to pass right now,” Barnes says. “Because of the divided Congress, we need Republicans to get on board, and we haven’t seen that yet. Many politicians talk a big talk about protecting coal mining jobs, but where they fall short is actually protecting the health of the miners. If our lawmakers aren’t supporting miners with black lung, then they are treating them like disposable cogs in a machine.”

Willie Dodson contributed to this article.

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests