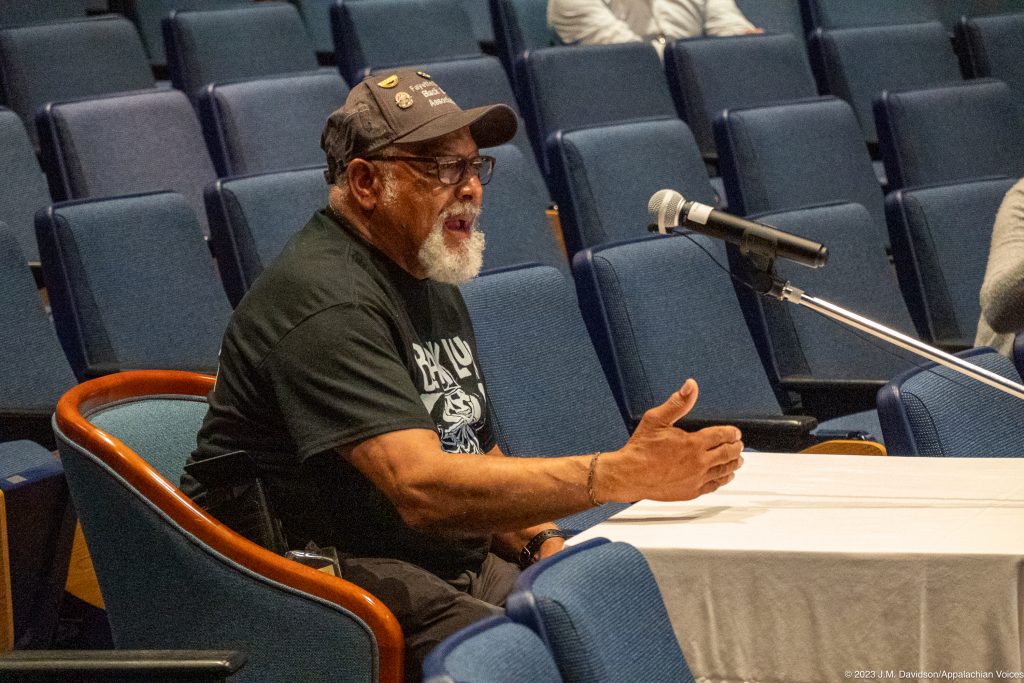

National Black Lung Association President Gary Hairston spoke about his experience living with black lung disease. Photo by J.M. Davidson

Tell MSHA: Strengthen the silica rule!

Some of the comments were technical, involving specific laws and regulations or mentioning medical science. Some were from advocates who work with current and former coal miners. Other testimony, like that of miners Terry Lilly and Gary Hairston, captivated the room with their emotional stories about living with black lung disease and witnessing mine operators cheat on dust sampling throughout their careers.

“We need to go to the source on this,” said Lilly. “I’m at 40% of my lung capacity. I’ve got 30 years of coal mining and I know the tricks and how they operate. I’m as guilty as any for hiding dust samples. Cheating the samples is what we need to stop. If we could stop that, we could save lives. … It’s too late for me. But I’d like these young people to be protected. One of these days they’ll be like me and can’t walk across the parking lot.”

“When I was in there, they told us that if we get bad samples, they will shut the mine down,” said Gary Hairston, a West Virginia resident and president of the National Black Lung Association. “I grew up in a coal camp, I know everything about coal mining, I’ve been around it my whole life. And I want to see something done about younger coal miners.”

Increased silica dust exposure is a significant driver in a decades-long surge in black lung disease in Central Appalachia. An estimated 1 in 5 tenured miners —those working at least 25 years — in the region have the disease, and 1 in 20 have the most severe form of black lung.

MSHA announced the proposed rule at the end of June, after advocates and members of Congress urged the Biden administration to release the long-awaited — and delayed — rule.

MSHA’s rule would for the first time ever create a silica testing and enforcement standard — separately enforced from general coal dust rules — that would require mine operators to make corrective actions to lower silica levels when they’re known to be high. Importantly, it will lower the permissible exposure level of respirable silica from 100 micrograms per cubic meter down to 50 micrograms, bringing the level for miners in line with all other industries. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health first recommended a 50 microgram silica exposure limit back in the 1970s.

Appalachian Voices and other black lung advocates have identified several weaknesses in the rule, however, including:

- An overreliance on mine companies to sample themselves at unclear and infrequent intervals

- Forcing miners to work wearing respirators, which have been known to fail, in hot, clouded and cramped conditions no matter how high the silica levels might be, rather than shutting production down until controls can be implemented

- A lack of monetary fines or penalties when silica exceeds the permissible exposure level and when operators don’t comply with the rules

A sign at the entrance of the MSHA Academy in Beaver, W.Va. Photo by Quenton King

The Beckley hearing started off with good news when Deputy Assistant Secretary Patricia Silvey announced that MSHA was extending the rule’s comment deadline 15 days, to Sept. 11. This is a far shorter extension than what many mining industry associations had been asking for in public comments since the rule was released. Appalachian Voices and other partners requested that MSHA avoid a lengthy extension that could further delay finalizing the rule, putting miners at continued risk of silica exposure and black lung disease.

Deputy Assistant Secretary Patricia Silvey moderated the silica hearing on Aug. 10. Photo by J.M. Davidson

He noted that the silica sampling requirements were both unclear and likely not frequent enough to adequately protect miners. Petsonk said that it’s shortsighted to rely on mine companies to sample themselves, when it’s known that companies have a history of fudging and faking sampling data, especially if there’s no penalty for high silica levels.

“A rule with no penalties is no rule at all,” said Petsonk. “[Coal companies] don’t understand the value of the blood and lives of miners. If they did, they would have enforced these laws willingly.”

Sam Petsonk, an attorney who assists miners with black lung claims, spoke about the rule’s weaknesses. Photo by J.M. Davidson

Vonda Robinson, vice president of the National Black Lung Association, spoke about the disease impacting younger miners.

“But now we’re looking at guys actually 32 and 34 years old getting complicated black lung,” said Robinson. “And that tells you that there’s something wrong with the coal companies. They’re not doing what they’re saying they’re doing.”

Several miners and advocates spoke about how difficult and dangerous it would be for MSHA to allow mine production to continue while silica levels are high so long as miners are wearing respirators. The rule as written says this should be temporary, but if there’s no clear definition of the word, advocates worry this would allow workers to work in dangerous conditions indefinitely. Miners shared how hard it is to hear each other when they’re wearing respirators deep in the mines, when they rely on verbal communication to keep each other safe.

“Respirators are a band-aid,” said Leonard Go, a University of Illinois pulmonologist. “In an ideal setting, where no miner has a beard, no miner has to do hard labor, and communication is not needed, respirators may be effective. In the real world respirators provide a false sense of security.”

Appalachian Voices Central Appalachian Field Coordinator Willie Dodson highlighted additional concerns with MSHA’s proposed silica rule. Photo by J.M. Davidson

“Ten or 20 years from now, we may look back at this process as the moment that we curbed this epidemic,” he said. “If MSHA gets this right, fewer miners will have to give up their health due to this disease. Fewer papaws will have to explain to their babies that they don’t feel well enough to play with them in the yard. … If we get this wrong, we’ll see no change in the rate of miners contracting black lung.”

How you can help

MSHA is accepting comments on the rule until September 11th, 2023. Appalachian Voices and Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center have a grassroots petition that outlines the concerns mentioned throughout this blog post, including a lack of financial penalties for mine operators and an over-reliance on and unearned trust in operators to sample and report their silica levels accurately. Please sign and share the petition!

You can also learn more by watching this webinar recording.

Leave a Reply