By Hannah Wilson-Black  Hannah Wilson-Black is serving Editorial Communications Assistant at Appalachian Voices during late summer 2021. Originally from northern Virginia, Hannah is a third-year student at the University of Chicago, where she studies Creative Writing and Environmental/Urban Studies. Hannah loves reading environmental memoirs and hopes to one day join the ranks of these formidable environmental writers!

Hannah Wilson-Black is serving Editorial Communications Assistant at Appalachian Voices during late summer 2021. Originally from northern Virginia, Hannah is a third-year student at the University of Chicago, where she studies Creative Writing and Environmental/Urban Studies. Hannah loves reading environmental memoirs and hopes to one day join the ranks of these formidable environmental writers!

What does energy democracy look like? It can look like a neighborhood full of solar panels in Puerto Rico, a community center powered by renewable energy in Central Virginia, or West Virginians buying power generated on former surface mining lands.

If “energy democracy” was a reality nationwide, every energy customer would have more control over:

- 1) what sources their energy comes from

- 2) where energy infrastructure is located

- 3) the cost of their energy

Energy customers are often subject to the decisions of monopoly utilities assigned to their areas by the state, but as the speakers in our three-part Energy Democracy In Action webinar series show, cheaper, more reliable, cleaner power is possible!

Our first webinar on June 29 (recording available here) was themed around how energy is produced. Guest speakers PJ Wilson and Javier Rua-Jovet of the Solar and Energy Storage Association of Puerto Rico, a renewable energy industry network, Gil Hough of Tennessee Solar Energy Industries Association, and Scott Sklar of The Stella Group Ltd, a clean energy optimization and policy firm, all provided examples of successful community solar projects.

Amidst Puerto Rico’s rapid transition to greater renewable energy following severe storms and the resulting power outages, Wilson said he has seen multiple instances of entire towns or neighborhoods signing up for solar projects, lowering the cost of installing panels for each individual household. Such projects are examples of microgrids, self-sufficient energy systems that serve local customers independently of the central grid.

Speaking of communities around the island that are building microgrids, Rua-Jovet said, “There’s a lot of energy self-determination going on … based on distrust of authorities and the utility and the lack of trust in the grid itself.” He gave the mountain town of Casa Pueblo as an example of a community “sophisticating itself by its own bootstraps and putting solar on community roofs.”

Gil Hough showed models of the Gaynor Solar Project, a community-backed shared solar array which is slated to begin construction in Pleasant Hill, Tennessee this fall.

“It’s been a long, hard battle,” Hough said of Pleasant Hill residents’ five-year fight for the project, but the small, rural Tennessee community was finally able to negotiate a financing arrangement called a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) with the Tennessee Valley Authority to build a community solar array on a resident’s farm. Pleasant Hill suffered from power outages for years, pushing them to look into community solar. Hough said he’s excited for Pleasant Hill to provide a model of “something good that can be duplicated” in other places.

Scott Sklar added that low-income communities have the most expensive and least reliable power, and thus have the most to gain from creating renewable microgrids to power houses and community facilities. On a related note, read about how the Solar Workgroup of Southwest Virginia is working to make shared solar available to Southwest Virginians—and how to get involved—here.

The second webinar in the series (recording available here) covered where energy infrastructure, such as methane gas pipelines and related compressor stations and power plants, is built and how unjust siting decisions can be changed. Speakers Joey James of consulting firm Downstream Strategies, Taylor Lilley of the nonprofit Chesapeake Bay Foundation, and Queen Shabazz of the nonprofit Virginia Environmental Justice Collaborative shared their energy democracy success stories.

James, a West Virginia native, noticed growing nationwide interest in large-scale solar years ago but was surprised to find that nearly all of West Virginia’s 550 square miles of former surface mine lands had not been repurposed for any economically productive projects, even though such open land is well-suited for solar developments. According to James, when he became more deeply interested in solar development in 2015, “Some of the largest solar developers had really no idea or interest in doing business in West Virginia or Central Appalachia at that time. They hadn’t even considered that we had a bunch of mine sites that could be perfect for solar.”

Solar-friendly West Virginia legislation supported by James and other advocates has met with some success in the West Virginia state legislature, with major bills passed in 2020 and 2021. As of this year, PPAs are legal in West Virginia and solar developers have plans to build a total of 5 GW worth of solar arrays, some of them on former mine sites!

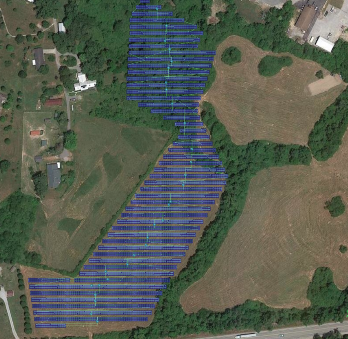

The Mineral Gap Data Center and Sun Tribe Solar, a Virginia-based solar company, are developing a 3.46-megawatt solar installation to power the data center on this former mine site. Photo courtesy of Downstream Strategies

Lilley, a lawyer with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, described the success story from Buckingham County, Virginia, where the community of Union Hill, a historically Black, Freedmen-built community, fought back against a proposed fracked-gas pipeline that would have involved a polluting compressor station in the center of the community.

Lilley is currently working with Charles City County residents, whose community was bombarded with proposals for two power plants — the C4GT and Chickahominy power stations — as well as a new portion of the existing Virginia Natural Gas pipeline. After the passage of new state laws and activism from Charles City County, plans for the C4GT station and the pipeline extension were eventually canceled.

“We were seeing this community take the burden of pollution without reaping any of the benefits,” Lilley said of Charles City County, which would not have been serviced by either of the power stations.

When the utility tells the story, Lilley said, they say whatever they need to to get energy infrastructure projects to move forward. So “community narratives are essential,” she said, “and there’s no way to move forward without those stories.” But their fight isn’t over, as the Chickahominy station is still attempting to move in.

Queen Shabazz of the Virginia Environmental Justice Collaborative works and lives in Petersburg, Virginia. During the webinar, she talked about the city’s success with installing solar panels on the roof of the Petersburg Community Resiliency Hub, a community center that can serve as an emergency shelter in the case of a power outage during the severe flooding Petersburg often experiences. Shabazz and fellow advocates are currently working to get a solar storage battery for the Hub, and she hopes that Petersburg residents will start seriously considering more community-owned solar projects, which she said will require hard work to persuade elected officials.

The Petersburg Community Resiliency Hub. Photo courtesy of Queen Shabazz, executive director of Virginia Environmental Justice Collaborative

We’ve talked about changing how and where energy is produced— next we’ll explore community control over how much energy costs. Join our third Energy Democracy in Action event coming up on August 31 at 5:30pm EDT to hear from more expert speakers about their struggles and successes in making energy affordable for everyone!

Register for the Aug. 31 webinar

Glossary

- Microgrid: a self-sufficient energy system that serves local customers independently of the central grid. Microgrids frequently include solar panels, small wind turbines and battery storage and increasingly include electric vehicle charging stations.

- Power Purchase Agreement (PPA): A financial agreement in which a third-party developer builds, owns, and operates a group of photovoltaic solar panels (for little or no cost) for a customer who hosts the panels on their property and purchases the energy generated for a predetermined number of years.

- Compressor station: A facility along the path of a natural gas pipeline that removes impurities from the gas and boosts its pressure level to make up for the pressure lost as gas is supplied to customers.

- Large-scale solar: Solar electricity-generating projects, usually mounted on the ground, which involve a large solar array and often serve commercial purposes. Also referred to as “utility-scale solar.”

- Solar array: A group of photovoltaic solar panels connected together in one system.

Leave a Reply