Willie Dodson | May 12, 2024 | No Comments

Elizabeth and Anderson Jones pose with an air monitor in their community near Chatham, Va. Photo by Jessica Sims

“Everything’s covered up with dust,” Nancy Owens of Aily, Virginia, said in December 2020. “It’s just really bad.”

Dozens, or even hundreds, of coal trucks were driving past Owens’ home each day, on their way from a nearby surface mine to a coal processing facility. As the trucks passed, they brought dust and mud into the community, which accumulated on and around the Owens’ residence.

For over four years, dust levels in the coal community of Aily have been at least partially controlled. After a series of complaints filed by Owens with the Virginia Department of Energy and subsequent reporting on the problem in The Appalachian Voice, Alpha Natural Resources installed a truck wash at the mine in question, alleviating the worst impacts of the dust for Owens.

But this outcome is the exception, not the rule. For decades Appalachian Voices, the nonprofit organization that publishes The Appalachian Voice, has worked with communities across the region dealing with excessive dust from coal mines and coal trucks. Rarely are these issues resolved until mining is completed or abandoned in the area.

In response to concerns like these and inconsistency in whether environmental regulators address them, Appalachian Voices began conducting air monitoring in mining communities in 2020. This work now encompasses dozens of partners in communities across five states.

The Upper South and Appalachia Citizen Air Monitoring Project launched in 2023 with funding from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency provided through the American Rescue Plan Act. Project partners installed small, easy-to-use devices that continuously monitor fine and coarse airborne particulate matter and make the data available to the public via a web map. Appalachian Voices analyzes the data quarterly and publishes brief reports for each device, which staff share with community partners, the EPA and others. As of spring 2024, about 40 monitors have been installed.

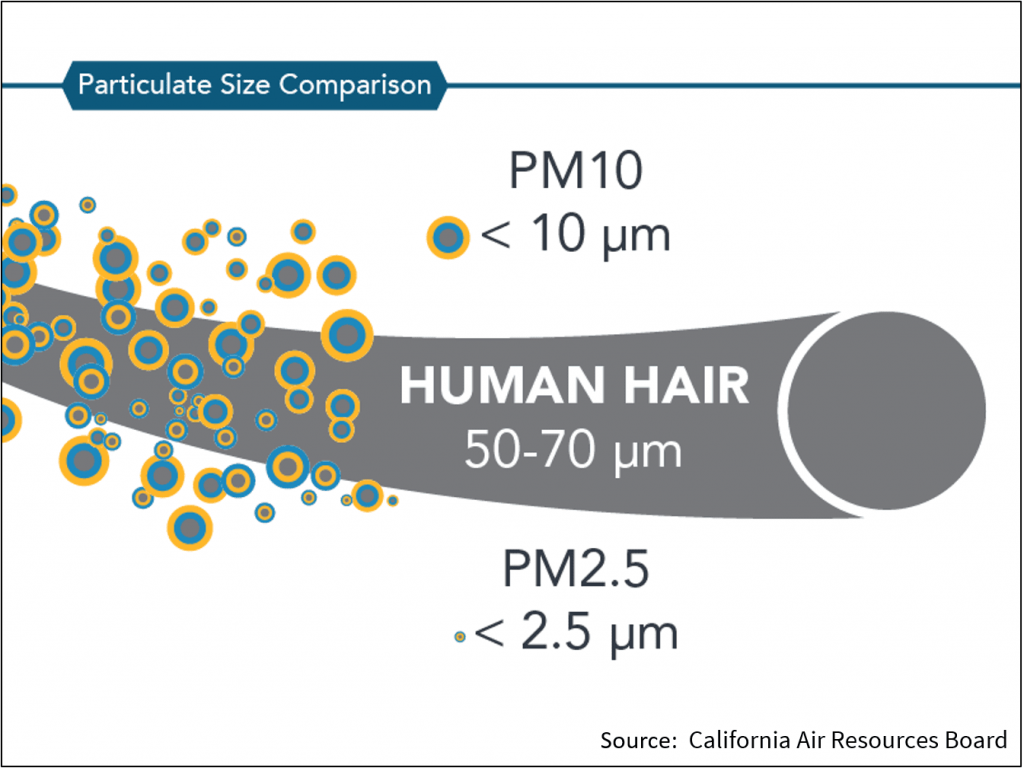

USACAMP is primarily focused on documenting levels of fine particulate matter, also known as PM 2.5, soot or fine dust from fossil fuel combustion, manufacturing, mining, transportation and other sources. Through a partnership with Virginia Tech, there will be a secondary focus on volatile organic compounds in two Southwest Virginia communities.

PM 2.5 kills nearly 100,000 people in the United States every year. It causes asthma attacks, hospitalizations and emergency room visits for cardiopulmonary diseases. It is also linked to cancer and premature deaths. Exposure to high levels of PM 2.5 hits Black and Brown communities the hardest. A recent Environmental Defense Fund study showed that Black Americans 65 and older are three times more likely to die from fine particulate pollution than White Americans of the same age.

PM 2.5 kills nearly 100,000 people in the United States every year. In February, the EPA lowered the National Ambient Air Quality Standard for PM 2.5 concentrations from 12 to 9 micrograms per cubic meter, measured as an annual average. In February, the EPA lowered the National Ambient Air Quality Standard for PM 2.5 concentrations from 12 to 9 micrograms per cubic meter, measured as an annual average. Graphic by California Air Resources Board

In February, the EPA lowered the National Ambient Air Quality Standard for PM 2.5 concentrations from 12 to 9 micrograms per cubic meter, measured as an annual average. This stronger standard would prevent 4,500 premature deaths annually by 2032, according to the EPA. The move was applauded by public health and environmental organizations, including Appalachian Voices, even though experts had recommended an even stricter limit. But the National Association of Manufacturers sued the administration and 30 Senate Republicans have co-sponsored a legislative effort to block the rule’s implementation.

The effectiveness of the new rule would depend in part on how well the EPA measures air quality and determines compliance with the national standard. In partnership with state regulators, EPA maintains a network of air monitors around the country, and uses the data from these monitors to determine an area’s compliance with the national standard. But most communities do not have EPA air monitoring stations, which means the official government data is full of blind spots.

Through USACAMP, Appalachian Voices and partners are now able to evaluate local PM 2.5 concentrations and compare them to the annual national standard.

USACAMP partners represent a diverse array of communities and concerns. About a third of the monitoring sites are located in coal mining communities. Another third are situated in areas where residents are concerned about other fossil fuel infrastructure, including power plants, natural gas compressor stations and a major coal export terminal. The last third are in communities with chemical and manufacturing facilities, major highways and other sources of air pollution. Next are a few snapshots of USACAMP communities and partners.

“We’re very proud of our farm and of our legacy,” says Elizabeth Jones, who, along with her husband Anderson, participates in USACAMP. “My husband’s family is Native American and native southerners. They’ve been here since before the British. Our family legacy is almost a hundred years old, and we are trying our best to use the land for the legacy it was supposed to be used for, which is agriculture.”

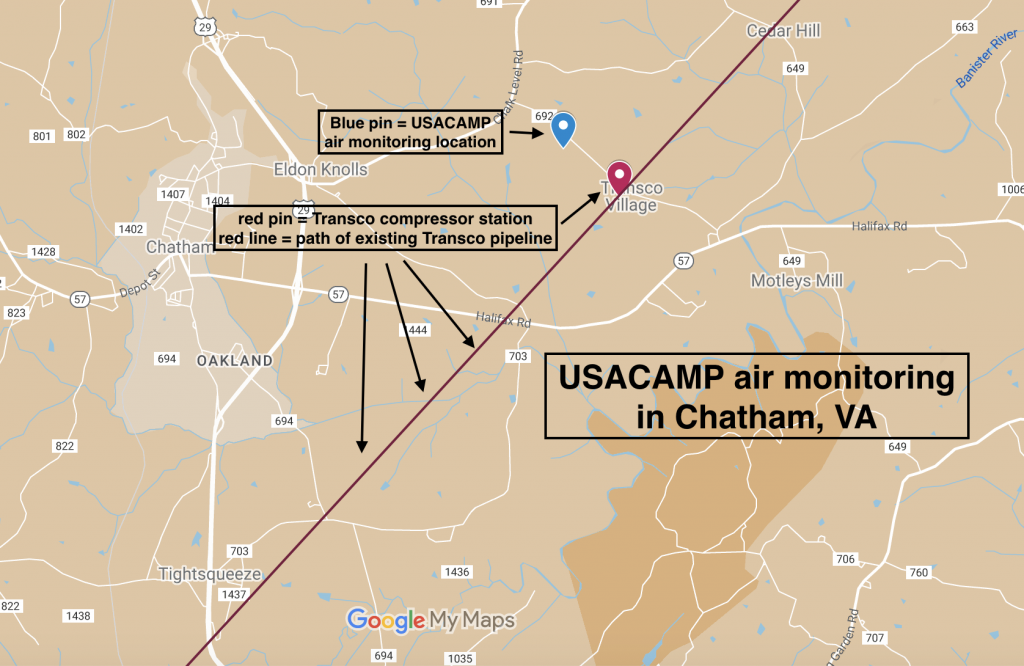

Concerned about local air quality due to the presence of multiple Transco fracked-gas compressor stations operating about a quarter mile from their home, the Joneses installed an air monitor on their property as part of the project in October 2023. The Transco stations began operating in the early 1960s and are part of the infrastructure for the Williams Transco methane gas pipeline, which runs from New York to the Gulf Coast. Transco recently announced multiple pipeline expansion projects, including the “Southeast Supply Enhancement Project,” which could involve expansion of a nearby station.

Compressor stations release numerous pollutants into the air, including PM 2.5, that are associated with a variety of adverse health impacts, according to research by faculty at the University of Virginia and other institutions.

“I have sinusitis,” Elizabeth Jones says. “I use a spray to breathe better. My husband has asthma.”

Jones is concerned that local pollution may contribute to these issues, and she is distressed by the lack of easily available public air quality data for her area. The closest PM 2.5 monitor maintained by state regulators is 42 miles away, and on the other side the Blue Ridge Mountains from Jones’ community.

In 2021, the Joneses faced an additional threat. The developers of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, which would traverse 303 miles through West Virginia and Virginia and terminate near the Jones’ home in Chatham, planned an extension called MVP Southgate. Developers recently redesigned MVP Southgate, but the earlier route would have crossed the Jones’ land and required another methane gas compressor station nearby.

Pittsylvania County NAACP is monitoring air quality roughly half a mile away from the Transco compressor station at Chatham, Virginia. Map by Willie Dodson.

The couple’s farm sits just east of the town of Chatham within the Banister District, which is majority Black per the 2020 Census. The impacts of pollution are disproportionately borne out by communities of color, a fact that is all too real for Elizabeth Jones.

“I’m African American, so I know that we’ve been unjustly treated in terms of some of the places where the government will put industrial [sites] without anybody having a say,” she says. “We have to stop [the pipeline] because this is more of the same. … Clean air and water and soil seem to be civil rights to me.”

The Joneses have long been environmental justice leaders in the region and are excited to be citizen scientists, advocating for their community’s health. The air monitor on their property will help evaluate particulate matter levels from ongoing and legacy pollution and provide baseline data if any existing compressor stations are expanded, or new stations are built.

Susan Vogt describes the neighborhoods of Latonia and Wallace Woods as “the heart of activism” in Covington, Kentucky, a small city across the Ohio River from Cincinnati.

“I’ve lived here for 40 years,” Vogt, a member of Kentuckians For The Commonwealth, says. “Covington is very mixed, and my neighborhood Latonia is very mixed. It’s mixed racially, economically, educationally — and this is one reason I like it. Usually neighborhoods are more divided. It’s a little bit unique here in that way.”

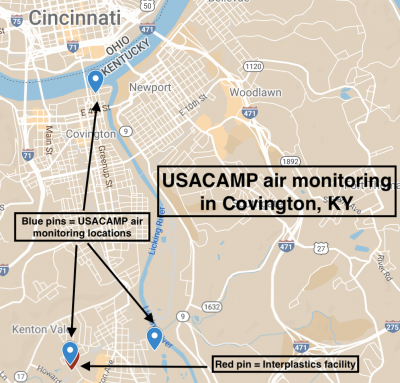

Kentuckians For The Commonwealth is a statewide grassroots organization that advocates for social, economic and environmental justice. KFTC’s projects are driven by their members, who are organized into local chapters across the state. For the Northern Kentucky chapter, which has members in Covington and nearby communities, emissions from a plastics manufacturing facility are a cause for concern, as is air quality generally.

After retiring from a career in the Catholic Church, Vogt sought opportunities to get involved with environmental activism. She was drawn to efforts to reduce single-use plastics, which led her to examine the plastics industry in her own backyard.

“Neighbors and friends … were concerned about what was happening at Interplastics,” Vogt says, adding that she lives about a mile from the plant. “People were asking some pretty serious and painful questions about, ‘does the existence of this plant in our area threaten our health?’”

KFTC has air monitors a few hundred feet and about a mile from the Interplastics facility, with a third in downtown Covington. Map by Willie Dodson.

Interplastics manufactures polyester, vinyl and other materials. Their facility in Fort Wright, Kentucky, which abuts Covington and the community of Latonia, has been the subject of scrutiny for many years.

In 1997, the company settled a lawsuit for $4.75 million with hundreds of community members who alleged that fumes from the operation were causing headaches and nausea. In 2019, a shelter-in-place order was issued to nearby residents after an incident caused a “chemical cloud” to waft into the community. Another shelter-in-place order was issued in 2022, after a report of explosions at the facility.

While styrene and other dangerous chemical emissions are of particular concern to those living near the Interplastics plant, fine particulate matter is also an issue. Vogt explains that KFTC members and others in her community want to know whether they are exposed to dangerously high levels of fine particulates, and how their level of exposure compares to levels in the United States as a whole.

If USACAMP air monitors in Latonia detect dangerously high levels of particulates, Vogt says community members can ask, “Is any of that related to being close to this Interplastics Plant?”

She adds, “If so, this has got to stop.”

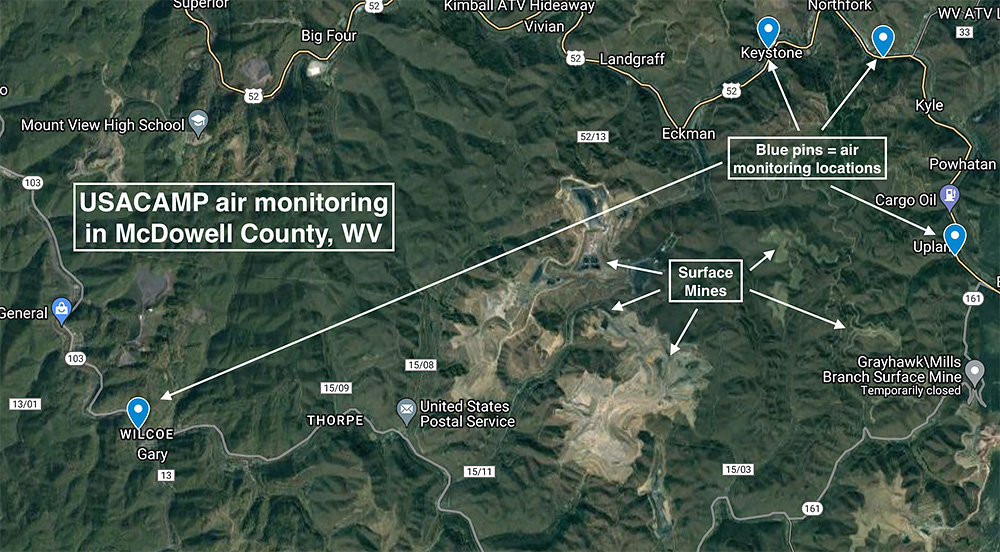

“When they blast, it becomes a plume. The plume falls down 15 minutes after each blast into our community,” said Timothy Hairston at a February 2024 community meeting organized by Friends for Environmental Justice. “That plume includes silica dust.”

Hairston is a minister who lives in the tiny community of Upland, near the town of Northfork in McDowell County, West Virginia. He contacted Appalachian Voices after reading about the organization’s support for a regulatory change intended to protect coal miners from high levels of respirable silica, a substance that causes the most severe form of black lung disease. Hairston was concerned about exposure to silica and other constituents of fugitive coal mine dust, not only for miners working in the mines, but for communities like his own, which are exposed to dust caused by blasting on nearby surface mines.

A hazy cloud of coal dust from the Blue Eagle Mine fills the air above a home in Upland, West Virginia. Photo courtesy of Timothy Hairston

Hairston’s home is immediately downhill from the Blue Eagle Surface Mine, a 450-acre mountaintop removal coal mine. On Valentine’s Day of 2023, Hairston was shocked to see a particularly huge plume of dust settling into his community. Several months later, he documented thick, black sludge flowing down the small stream behind his house, which originates within the Blue Eagle Surface Mine boundary.

In response to Hairston’s sludge complaint, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection issued a citation, prompting the company operating the mine to reroute runoff so that it no longer flowed into Upland.

But DEP did not cite the Blue Eagle Surface Mine over the dust incident, stating that they found no evidence of any infraction. In their investigation of the dust complaint, DEP referenced a 2012 report by the research organization Battelle Memorial Institute, claiming that surface mining did not cause dust levels to exceed health standards. This study is often cited by DEP, but it only looked at particulate levels in one community where surface mining was occurring, measured over a two-week period 12 years ago.

Appalachian Voices has air monitors across McDowell County, W.Va., where the mining, processing and transportation of coal releases dust into communities. Map by Willie Dodson

Unsatisfied with DEP’s findings, Hairston is now participating in USACAMP with an air monitor at his home to document potential spikes in fine particulate matter corresponding with blasts on the Blue Eagle Surface Mine.

“We’ve had six deaths right there where I live, all next door to each other,” Hairston says. “In the summertime, we sit out on our porches. We have picnics. We gather together. And they blast, and that dust is inside of us … It’s sad what they’ve done to us.”

In February, West Virginia lawmakers introduced a bill supported by polluting industry lobbyists that would have prohibited the DEP from examining data collected by community air monitoring programs, such as USACAMP. The bill passed the state House but died in the Senate.

Even if a similar bill later becomes law, data from the monitoring device at Hairston’s home, and the dozens of other USACAMP monitoring locations across the region, will be shared directly with the EPA, which maintains oversight authority over state air quality programs.

To review data collected by the Upper South and Appalachia Citizen Air Monitoring Project, visit appvoices.org/usacamp.

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests