Molly Moore | December 5, 2012 | No Comments

By Brian Sewell

Less than a month after the Nov. 6 elections, Republican Rep. Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia announced that in 2014 she would seek the U.S. Senate seat currently held by Democratic Senator Jay Rockefeller. Although Rockefeller has not yet announced if he will seek another term, the effect of a divisive election in which the Appalachian coal industry played a key role might have already given Capito an edge.

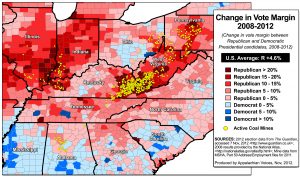

Between the 2008 and 2012 presidential election, the Republican party gained in 95 percent of coal counties in the United States. Maps of the partisan shift reveal the price the administration paid for EPA actions that were strategically portrayed as a political "war on coal." Map produced by Appalachian Voices

For decades, Rockefeller has been an advocate for coal miners and mining. In the months leading up to the election, however, he commented on the harsh truths that the coal industry must face, including declining demand and negative health impacts, and criticized what he called “scare tactics” about a political “war on coal” as a “cynical waste of time, money and worst of all, coal miners’ hopes.”

As a result, the coal industry and its allies — including Capito, who recently said that she plans to continue fighting the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s “dangerous and unconstitutional crusade to dictate our nation’s energy policy” — have implicated Rockefeller in the political battle over coal that his remarks aimed to rectify.

Coal has always played a role in deciding who gets elected in Appalachia. This time around, it seemed, politicians either chose a side or one was chosen for them.

Campaigning for Coal

Appalachia is a bastion of swing states. Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia have 89 electoral votes that can be won or lost. Each of these states has changed hands at least once in presidential elections since 1996, with the exception of Pennsylvania, which has remained narrowly Democratic.

Swing state voters’ concerns and attitudes receive the attention of candidates and their campaigners, and a handful of states — many of which produce coal — can decide who becomes president. But outside spending groups and political action committees also target decisive states, and they spend big on the political advertising and media coverage that affects public understanding of issues.

Although largely driven by market forces, the coal industry’s downturn has been strategically portrayed as the result of actions by the Obama administration and the EPA. And although the “war on coal” rhetoric was not enough to make Barack Obama a one-term president, the message of regulations suppressing economic opportunity resonated with voters in areas facing layoffs and high unemployment.

One example of where the strategy is paying dividends is Boone County, W.Va., which produces more coal than any other county east of the Mississippi River. Of the 3,410 counties in the United States, Boone saw the largest pro-Republican swing, approximately 42 percent, between the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections. The same pattern was seen in southwestern Virginia, where the already GOP-leaning vote margin in the six coal-mining counties swung further in favor of Republicans by 24 percent.

The “war on coal” message was also used to target incumbents running in coal-producing congressional districts. In Kentucky’s 6th district, Democratic Rep. Ben Chandler lost to challenger Andy Barr after a heated campaign in which Barr succeeded in linking Chandler to the Obama administration. Coal-friendly donors and political action committees backed Barr; nearly $4 million was spent on television ads in Lexington, Ky., most questioning the other candidate’s allegiance to coal.

In states including Pennsylvania and Ohio, industry-endorsed candidates were defeated in several key U.S. Senate races. In a highly contested race in Virginia between Democrat Tim Kaine and Republican George Allen, more than 60 percent of the $53 million spent by outside groups benefited Allen. Ultimately, Kaine defeated Allen by a margin of 20,000 votes, helping the Democrats retain a slim majority in the Senate.

On Different Terms

Although the United Mine Workers of America did not endorse either presidential candidate, outspoken coal executives and union members made it clear that they were very concerned with the results of the election. Less clear, however, was a substantiated explanation of why their fears were contingent upon its outcome.

According to analysts, new regulations are not to blame for coal’s downturn. Instead, the coal industry is suffering due to competition from cheap natural gas and declining demand paired with rising production costs. Operators in Appalachia are especially at risk in this new market reality. Though, as Associated Press reporter Vicki Smith wrote, “it’s easier to call the actual forces reshaping coal a political or cultural ‘war’ than to acknowledge the world is changing, and leaving some people behind.”

In the weeks after his re-election, the coal industry portrayed the anti-Obama voting trends in coal-mining states as a backlash against the economic impact of EPA rules on miners and their families. In most areas, however, mining jobs have not declined, even though demand for coal has dropped precipitously. Under the Obama administration, coal mining employment in West Virginia increased, and remains higher than most of the past decade, despite layoffs in 2012.

As for the much-vilified EPA, the agency has so far been lenient on the implementation of regulations that could impact coal-burning utilities by extending compliance deadlines and often choosing to delay or even jettison proposed rules altogether.

Fundamental changes in the United States’ energy landscape and challenges endemic to the Appalachian coal industry have contributed to a shift in the politics of the region. Regardless of market and regulatory uncertainty, if Appalachian leaders want results, it will take more than criticizing the EPA to improve the region’s economic outlook.

Part of that will mean going beyond the “war on coal” rhetoric and accepting the realities of coal’s changing role in America. Or as former West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd said in one of his last public statements before his death in 2010, “To be part of any solution, one must first acknowledge a problem.”

The politics of Appalachia are closely tied to coal mining and its impacts on the land and the people. In upcoming issues of The Appalachian Voice, we will continue to explore the connections between Appalachian politics, energy policy and the environment.

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests