Brian Sewell | October 16, 2015 | No Comments

By Brian Sewell

Almost everyone agrees: the Clean Power Plan is a game changer. In form and function, the recently finalized regulations take an innovative approach to incentivize states to reduce carbon dioxide pollution and invest in cleaner energy.

Beyond that, arguments about the Clean Power Plan are often deeply colored by politics and disconnected from the plan’s intention or expected outcomes.

Developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the plan is the centerpiece of the Obama administration’s efforts to combat climate change and cut power plant carbon dioxide emissions that contribute to it.

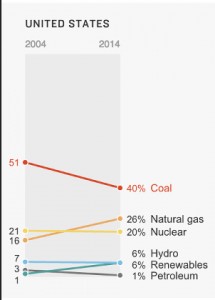

The plan sets custom pollution-reduction targets for states based on their existing energy mixes and emissions. It also encourages states to come up with their own approach to reach those targets. By 2030, the EPA hopes to see nationwide emissions drop 32 percent below what they were in 2005.

From President Obama’s perspective, “It’s not radical.” After all, dozens of states had already either established market-based programs to cut carbon emissions or set renewable energy goals prior to the rule’s release.

“Washington is starting to catch up with the vision of the rest of the country,” President Obama told a White House crowd the day of the Clean Power Plan’s release. “And by setting these standards, we can actually speed up our transition to a cleaner, safer future.”

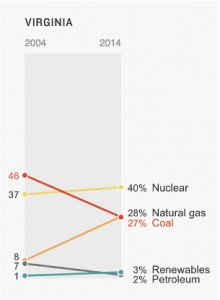

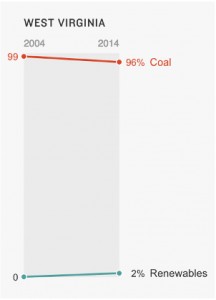

“How Each State Generates Electric Power (2004-2014),” graphics by Christopher Groskopf, Alyson Hurt and Avie Schneider/NPR

But in many central Appalachian states, policymakers remain adamant in their opposition. Claims of skyrocketing energy costs and economic ruin that began long before details of the final plan became clear are still frequent talking points.

“The battle continues,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) wrote in a September newsletter. “I’ve fought this administration and its EPA every step of the way in the President’s war on coal, and I don’t intend to stop now.”

It’s no surprise that the technical details of the plan, namely its achievability and the compliance options available to states, have not gotten as much coverage as the political reactions. But between those highly oppositional stances is the spectrum of actions already being taken by states to either challenge the EPA or find ways to realize the Clean Power Plan’s potential.

How Each State Generates Electric Power (2004-2014),” graphics by Christopher Groskopf, Alyson Hurt and Avie Schneider/NPR

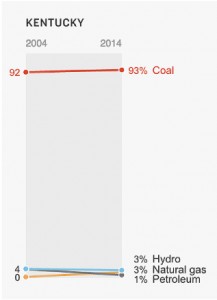

The final Clean Power Plan came at the height of summer and, in the Bluegrass State, a heated gubernatorial race. Candidates for both parties strongly oppose the plan and have pledged to ignore it if elected. Kentucky Attorney General Jack Conway, who is also the Democratic nominee for governor, sued the EPA in an attempt to prevent the agency from finalizing the plan and, more recently, joined an effort to prevent the final rules from taking effect. The commonwealth’s current governor, Steve Beshear (D), hardened his opposition after reviewing the final rule, which increased the emissions Kentucky is required to cut. Still, analysts say that even without the Clean Power Plan, Kentucky is on track to meet its emissions target a decade early because of coal plants already scheduled to retire.

“How Each State Generates Electric Power (2004-2014),” graphics by Christopher Groskopf, Alyson Hurt and Avie Schneider/NPR

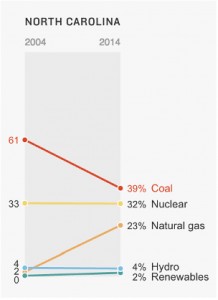

North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory (R) has been outspoken in his opposition to the Clean Power Plan and has vowed to fight it in court. But Donald van der Vaart, the secretary of the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality, has led the state’s charge. In an op-ed for the News & Observer, van der Vaart characterized the plan as a “one-size-fits-all” program and criticized state Attorney General Roy Cooper for encouraging lawmakers to develop a compliance plan. The state legislature, which is dominated by Republicans, seems somewhat divided on the best path forward. In April, the N.C. House of Representatives approved a bill to establish a stakeholder group and direct DENR to begin preparing a plan to comply. A few months later, a Senate committee voted to bar the state from writing a plan.

How Each State Generates Electric Power (2004-2014),” graphics by Christopher Groskopf, Alyson Hurt and Avie Schneider/NPR

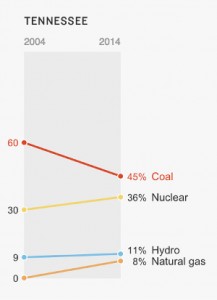

Unlike his counterparts in surrounding states, Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam (R) has said little about the substance of the Clean Power Plan or discussed the state’s approach to compliance, even after 20 state legislators sent a letter to the governor urging him to defy the EPA. This silence may be due to how the final Clean Power Plan treats nuclear power plants currently under construction. Under the final plan, soon-to-be completed nuclear facilities like the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Watts Bar Unit 2 can play a larger role in compliance. Other factors that have positioned TVA to meet Tennessee’s emissions goal include the utility’s recent long-term planning process and a historic Clean Air Act settlement in 2011 that forced a spate of coal plant retirements that continues today. As a result of that agreement with the EPA, a TVA spokesperson said the Clean Power Plan “won’t have much impact at all,” on the utility’s plans for its coal and gas fleet.

“How Each State Generates Electric Power (2004-2014),” graphics by Christopher Groskopf, Alyson Hurt and Avie Schneider/NPR

UPDATE: Shortly after this story went to press, Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe published an op-ed in the Richmond Times-Dispatch adamantly supporting the Clean Power Plan for creating “a pathway for clean energy initiatives that will grow jobs and help diversify Virginia’s economy.”

Gov. Terry McAuliffe (D) welcomed the Clean Power Plan and said he looks forward to “creating the next generation of clean energy jobs” in Virginia. Even Dominion Virginia Power, the state’s biggest power generator, commended the EPA for easing Virginia’s emissions targets and pledged to work with state agencies toward a compliance plan. But some Virginia policymakers remain skeptical. In an August op-ed for The Virginian-Pilot, state delegates Israel O’Quinn and Scott Taylor promoted legislation that would require the General Assembly’s oversight and approval of Virginia’s compliance plan because Gov. McAuliffe is “working to develop a plan without input from hard-working Virginians.” To the contrary, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality began a series of listening sessions across the state in September to gather general input from the public, placing a special emphasis on low-income communities and areas most vulnerable to climate change.

“How Each State Generates Electric Power (2004-2014),” graphics by Christopher Groskopf, Alyson Hurt and Avie Schneider/NPR

Days after the final plan’s release, West Virginia and 15 other states asked a federal court to block the rule until all legal battles are resolved and ensure “no more taxpayer money or resources are wastefully spent in an attempt to comply with this unlawful rule.” But the secretary of the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, Randy Huffman, is wary about refusing to develop a compliance plan. “You won’t have a seat at the table if you just say no,” Huffman told West Virginia Public Broadcasting in August. A new state law requires the DEP to complete a “comprehensive analysis” of the Clean Power Plan’s impact on West Virginia by early 2016.

Officials say that new nuclear facilities and state policies driving solar growth will make reaching Georgia’s emissions targets relatively easy. Despite sharply criticizing the draft rule, Public Service Commission Chairman Chuck Eaton says his state is moving forward to craft a compliance plan and the Georgia Environmental Protection Division will hold a public hearing to review the final rule in October.

Pennsylvania has taken a proactive approach to the Clean Power Plan and the state Department of Environmental Protection is pushing to submit a compliance plan by next September. The state’s Republican-controlled legislature will also have a say. A law signed before Gov. Tom Wolf (D) took office gives lawmakers the ability to review and revise any proposal the state submits to the EPA.

Similar to stakeholders in Tennessee, South Carolina officials were pleased that under-construction nuclear capacity can now count toward compliance. But that concession was not enough for the Attorney General Alan Wilson, who believes the Clean Power Plan is unconstitutional. Meanwhile, the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control is convening utilities, regulators and the public to develop a plan.

As a member of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a northeastern carbon-trading market, Maryland is well-positioned to meet its Clean Power Plan goal. The state is also committed under a 2009 law to reducing greenhouse gas pollution by 25 percent by 2020 — two years before the interim deadline set by the Clean Power Plan.

Like this content? Subscribe to The Voice email digests