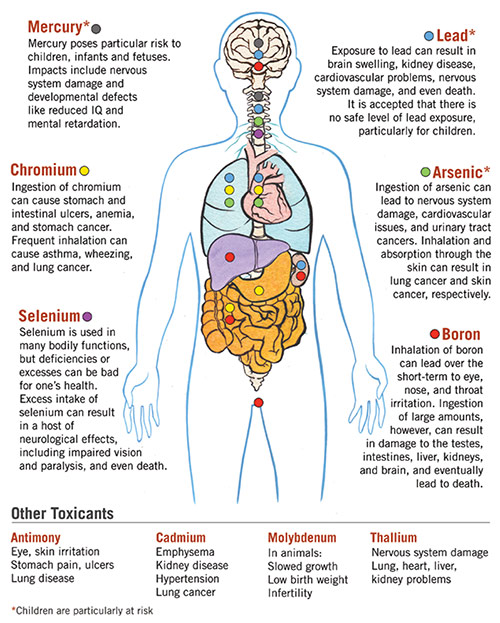

Coal ash is the waste produced when coal is burned for electricity. It consists of both fly ash, which is captured by “scrubbers” in the smokestacks to prevent air pollution, and bottom ash, which settles to the bottom of the furnaces. Coal ash contains 25 heavy metals, including arsenic, mercury, lead, selenium and chromium, as well as other toxic chemicals. Every year, U.S. power companies generate and have to dispose of millions of tons of coal ash nearly 130 million tons in 2014 alone.

Coal ash is everyone’s problem

Even if you don’t live immediately next to a coal ash impoundment, the potential that coal ash could contaminate your drinking water or your favorite rivers and lakes is a very real threat.

More than 1,400 coal ash impoundments holding trillions of tons of toxic coal ash are scattered around the country. Half of the ponds have no liner, 70% are located in low-income communities, and more than 200 are known to have contaminated nearby waters.

The Southeast is particularly vulnerable, with vast water resources, lax regulations, and almost 450 coal ash ponds with a capacity to hold more than 118 billion gallons of coal ash. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 21 of the nation’s 45 high-hazard coal ash dams are in the Southeast, meaning that a dam break would likely cause human death.

North Carolina alone has 33 coal ash impoundments located at 14 power plants around the state. It’s been known that impoundments at all 14 sites have been leaking, yet for years neither state regulators nor Duke Energy, which owns all the sites, have done much to address the issue.

How is it stored?

Typically, electric utilities mix their coal ash with water to form a sludge that is stored in huge impoundments, or ponds, that range from dozens to hundreds of acres in size. Sometimes it is stored in dry landfills. Either way, most ash pits don’t have liners, which are required for municipal garbage landfills to prevent toxins from leaking into groundwater. And most coal ash ponds are decades old and have poor infrastructure, raising the stakes of catastrophic failure, as in the case of the Kingston coal ash spill in Tennessee and the Dan River spill in North Carolina.

What are the health impacts?

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has found that people living next to an unlined, wet coal ash pond that is mixed with other coal waste, and who rely on a well for drinking water, have a one in 50 chance of getting cancer due to arsenic exposure. That’s nine times higher than the risk of cancer for someone who smokes a pack of cigarettes a day. Communities near coal ash sites also face increased risk of lung and heart problems, developmental issues, stomach ailments and premature death.

In communities near sites storing dry coal ash, the powder-like ash blows off of landfills and trucks that haul it from one place to another and becomes a dangerous source of air pollution that can lead to breathing and lung issues.

VIDEO: In March 2014, Annie Brown from Stokes County, N.C., home to the biggest coal ash pond in the state, spoke out about health issues in her community. She passed away that November.

How is coal ash regulated?

Without a federal law, coal ash management was up to the states, and most of them had fewer restrictions than for household garbage disposal. In 2000, the EPA began to draft the first-ever federal rules, but it was slow going.

In 2010, the agency proposed two regulatory options under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). One proposal would regulate coal ash as a hazardous substance, while the other would classify it as a non-hazardous substance, with far fewer requirements. Despite the known environmental and health hazards, and despite a growing outcry from citizens around the country for the strongest possible protections, the EPA’s final rule in 2014 classified coal ash as non-hazardous.

The rule contains several good measures — for example, new or expanding sites must be lined and have leachate collection systems, and utilities must monitor and control ash dust at each site. However, the rule notably fails in any enforcement mechanism. States are not required to adopt and implement the new standards, nor is there any permitting program that would enable enforcement.

North Carolina

Even before the Dan River disaster in February 2014, Appalachian Voices was connecting with communities around several of the larger coal ash sites in North Carolina, primarily Walnut Cove, near Duke Energy’s Belews Creek power plant, and Belmont, near Duke’s G.G. Allen plant. Our aim was to ensure residents had access to complete information about coal ash, not just what Duke or state officials chose to tell them. These communities began organizing and forming local groups to reach out to even more neighbors, and asking officials tough questions about the threats.

After the spill, these communities and many others around the state rose up to demand that the legislature, state agencies and Duke Energy resolve the coal ash crisis around the state. Appalachian Voices continues to work with these communities, as well as other social justice and public interest groups, to keep the pressure on.