By Matt Wasson

issued their long awaited proposal for new rules on how to regulate the disposal and storage of coal combustion waste (CCW), the byproduct of coal-fired power plants.

issued their long awaited proposal for new rules on how to regulate the disposal and storage of coal combustion waste (CCW), the byproduct of coal-fired power plants.

Since December of 2008, when more than 1 billion gallons of toxic coal ash spilled into the Emory River from a breached impoundment at the TVA’s Kingston Fossil Plant, environmental and industry groups have been waiting with tense anticipation to see how the Administration will approach regulating this highly toxic waste.

As it turns out, they’re still waiting. The EPA actually issued two proposals which, as James Bruggers of the Louisville Courier-Journal reported, can be simply (though far from completely) summarized as follows:

One approach would eventually phase out coal ash storage ponds. The other would would allow ash ponds, but only if they have plastic liners.

The EPA will decide which of those approaches to adopt following a 90-day public comment period that began yesterday. While EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson heralded the action as “the first-ever national rules to assure the safe management and disposal of coal ash,” reporters like Bruggers and Ken Ward at the Charleston Gazette saw EPA’s announcement as more of a “punt.”

Environmental groups had a mixed reaction, expressing enthusiasm for the EPA’s overall 563-page analysis, which, despite Jackson’s apparent ambivalence, provides enormously compelling scientific evidence that should favor the more stringent proposal for regulating CCW under hazardous waste provisions of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. But groups also expressed some frustration at the Obama Administration’s unwillingness to follow the EPA’s analysis to its logical conclusion.

But whichever path the EPA ultimately chooses, Big Coal scores thanks to an issue that was entirely excluded from the scope of both proposals: the virtually unregulated practice of dumping CCW into abandoned mines.

To mix a metaphor, in the great 90-day EPA Coal Ash Bowl that began with a punt, the environmental and public health team is down a star player and Big Coal has the ball on the 50 yard line. It ain’t over, but it’s gonna be a rough game.

Dumping coal ash waste into abandoned mines- “Beneficial” for whom?

The industry backlash against any regulation of CCW disposal has long centered on the issue of “beneficial use,” which typically implies using CCW to manufacture wallboard and other construction materials.

According to its promoters, minefilling is a “beneficial use” because CCW is alkaline and, at least the theory goes, dumping it into abandoned mines will neutralize the acidic mine drainage from active and abandoned mines.

The problem with this theory is that there really isn’t any good science to back it up. A study on the water quality impacts of minefilling published by the Clean Air Taskforce in 2007 provided an excellent test of how “beneficial” the dumping of CCW into mine pits actually is. As explained in a more recent and comprehensive report by Earthjustice:

…in two-thirds of all the mines studied, the introduction of coal combustion waste resulted in more severe, long-term water quality contamination than had ever existed at these sites from the mining operation itself. Furthermore, as a practical matter, dumping large quantities of CCW directly into water tables in highly fractured sites under massive quantities of mine overburden makes the prospect of cleaning up resulting contamination far more daunting than halting leakages from conventional landfills and ash ponds.

The pressure on the administration from industry to not designate CCW as a hazardous waste was intense because of the stigma it would put on the use of CCW for “beneficial use” purposes. The unprecedented extent of that pressure from the coal industry was underscored in a letter to the White House signed by 239 public interest organizations from across the country in April. According to the letter:

Industry groups that oppose mandatory federal standards have had nearly 30 meetings with OMB [Office of Management and Budget] on this rule – more than ever before on any single topic. These groups continue to present unfounded claims of power plant closures and exaggerated cost estimates as “fact,” thereby fomenting widespread but unwarranted fear of EPA regulations.

Wait… The coal industry presented exaggerated cost estimates to foment unwarranted fear of EPA regulations? Well I never!

That pressure was clearly effective in that, even if EPA chooses to regulate CCW under the hazardous waste provisions, it will not be labeled “hazardous” so as to avoid the dangerous connotations implied by the label.

But the industry pressure was equally effective in taking regulatory control of minefilling out of the hands of EPA scientists, who are no doubt well aware of the bad science underlying the practice and who are generally very serious about their job of protecting public health. In fact, the EPA already weighed in on the issue:

We believe that certain minefilling practices have the potential to degrade, rather than improve, existing groundwater quality and can pose a threat to human health and the environment.

It’s statements like this that apparently disqualified the EPA from regulating minefilling, which instead will be subject to a subsequent rule-making process headed up by the Office of Surface Mining, Reclamation and Enforcement (OSM). No timeframe was mentioned for when that rule-making would be initiated.

Putting OSM in charge of developing minefilling regulations, even with input from the EPA, is a huge victory for polluters for a number of reasons. First, the OSM is led by Joseph Pizarchik, nick-named “Coal Ash Joe” by community organizations in Pennsylvania for his unwavering support of minefilling when he was director of the Bureau of Mining and Reclamation in that state. Second, the “scientists” at OSM are a very different breed than those at the EPA.

OSM scientists are generally trained in “reclamation science” at one of the big mine engineering programs at schools like West Virginia University and Virginia Tech. The fundamental premise of reclamation science can be summed up in a statement from Dink Shackleford, past executive director of the Virginia Mining Association, who often said: “We have a chance to improve on God’s creation.” The science of mining and reclamation starts with a fundamental premise that must not be questioned- that no matter how toxic the pollution, how much mountain we blast away, that we can engineer nature back to as “good as new” or even better.

Viewed through this distorted lens, replacing the remarkably diverse and productive Appalachian hardwood forests with a barren plain covered in exotic grasses dotted with a few pines becomes an ecological benefit because it “improves forestry;” burying the headwaters of streams in millions of tons of mine waste is an ecological benefit because it “helps regulate stream flow;” and the virtually unregulated dumping of mine waste into abandoned mines is a “beneficial use” of coal ash.

There is a lot at stake for the coal industry in how minefilling is regulated because, according to the Earthjustice report (pdf), the cost of disposal in minefills is 89-95% less than the cost of disposal in engineered landfills. Also according to Earthjustice, about 25 million tons of CCW – 20% of total annual production – is disposed of in abandoned mines. While the EPA estimates that minefilling accounts for just 7% of CCW disposal, Earthjustice explains that the discrepancy is because, “industry and state regulators are hiding CCW dumping in mines behind the labels ‘beneficial use, or ‘recycling.'”

This minefilling loophole will become all the more important as EPA rules make regulated disposal of CCW more expensive. As the financial incentives for utilities to exploit this loophole become stronger, the pressure on the Obama Administration to delay action on minefilling, or to implement weak regulations, will become even more intense. Given that current regulations in most states for CCS minefilling are considerably weaker than regulations on disposal of household garbage, minefilling could quickly become the predominant method for CCW disposal.

How Does Minefilling Affect Health and the Environment?

The lede and photo from a story in the Miami Herald from November, 2009, helps put the health hazards associated with coal ash into perspective:

“When I was pregnant, I was dizzy, vomiting and could barely walk,” said Maximiliano’s mother, Anajai Calcano, 20. “My tooth cracked and fell out. Then my baby was born like that, without arms. Nothing like that had ever happened here before.”

By “before,” Calcano means before a U.S. power company’s coal ash arrived at a nearby port, sitting there for more than two years.

The story goes on to tell how citizens of Arroyo Barril in the Dominican Republican are suing a Virginia-based energy company for a variety of health problems they say resulted from the illegal disposal of coal ash on the shore of the town. The phrase “health problems” hardly does justice to the godawful deformities found in children born of mothers who had abnormally high levels of arsenic in their blood, one of many toxic metals associated with coal ash. Those “health problems” ranged from cranial deformities to missing limbs to organs outside their bodies.

The situation in Arroyo Barril is an extreme example, but it illustrates the general problem of toxic metal contamination of both air and water near coal ash disposal sites. The composition of coal ash includes a high concentration of toxic metals found in coal including arsenic, selenium, chromium, lead and thallium. While conventional disposal of CCW in wet impoundments has had demonstrable impacts on water quality, the practice of minefilling makes the problem of groundwater contamination far worse. According to the Earthjustice report:

The unique geologic characteristics of mines maximizes the risk of contamination from coal ash dumping. Mining breaks up solid rock layers into small pieces, called spoil. Compared to the flow through undisturbed rock, water easily and quickly infiltrates spoil that has been dumped back into the mined-out pits. Fractures from blasting become underground channels that allow groundwater to flow rapidly offsite. Because mines usually excavate aquifers (underground sources of water), the spoil fills up with groundwater. Unlike engineered landfills, which are lined with impervious membranes (clay or synthetic) and above water tables by law, coal ash dumped into mine pits continually leaches its toxic metals and other contaminants into the water that flows through and eventually leaves the site.

There are many cases where water contamination has already been found, according to the Clean Air Taskforce study of 15 minefilling operations in Pennsylvania.

So what’s next?

To be fair to the administration, the EPA specifically referenced a 2006 report on minefilling from the National Academy of Sciences as one of the documents that should guide the rule-making on minefilling. The recommendations of that report, as summarized by Earthjustice, include:

* Generators should pursue safe reuse of coal combustion waste ash before minefilling;

* Disposal sites must be investigated to determine the quality and location of groundwater, groundwater flow paths, the potential for coal ash to react with minerals or groundwater, etc.;

* Coal ash must be kept out of groundwater;

* Monitoring must be designed to detect movement of coal combustion waste contaminants;

* Deeds must record and fully disclose that coal combustion waste was disposed at the mine site;

* Bonds must be adequate to clean up any groundwater damaged by coal combustion waste disposal;

* Public input must be solicited in the development of national regulations and permits issued pursuant to those regulations.

If all of those recommendations were turned into regulations, the problems associated with minefilling would be largely alleviated. But the success of industry in stripping the EPA of regulatory oversight of minefilling provides little confidence that the administration will ignore that pressure when it comes to developing regulations on minefilling.

An even greater concern is that the industry will successfully delay rule-making on minefilling for another decade, the way they were able to delay disposal regulations for years until the TVA disaster woke people up to the hazards of unregulated coal ash storage. If their delay tactics are successful, the financial advantages of minefilling will make it the predominant method of coal ash disposal within a matter of years.

And if the momentum generated by the TVA disaster to regulate coal ash disposal is lost, it’s terrifying to think what the next disaster will be that would be needed to motivate agencies to action in the face of enormous industry pressure. As Lisa Evans, an attorney with Earthjustice who has tracked coal ash issues for nearly a decade, told the media in January:

Minefilling coal ash is a slow-motion and invisible counterpart to the TVA catastrophe. There, the destruction was unleashed in a matter of minutes. For communities with water poisoned by the country’s hundreds of coal ash mine dumps, the damage has been gradual and largely unseen, but it also presents a grave threat.

People in coal mining regions have suffered pollution of their water and air for decades, and with the EPA finally beginning to crack down on mountaintop removal mining and the disposal of mine waste into streams, what a tragic irony it would be if pollution from valley fills was replaced by even greater pollution from minefills. That’s the way it’s headed, and it’s going to take the involvement of thousands of Americans to counter the coal industry’s powerful pressure to keep regulations weak or nonexistent.

This is no time to sit on the sidelines – there are 89 days in the EPA’s Coal Ash Bowl, and your help is needed now.

[UPDATE: The link to take action above, “your help is needed now,” is not yet set up by the EPA – I will update again as soon as the EPA gets it straightened out]

Follow Matt Wasson on Twitter: www.twitter.com/forthemountains

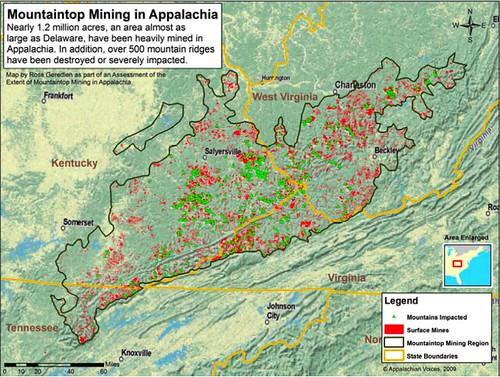

Last April, the EPA announced new guidance standards for new and pending surface mine permits in Appalachia. EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson stated “Coal communities should not have to sacrifice their environment or their health or their economic future to mountaintop mining. They deserve the full protection of our clean water laws.” The Administrator proclaimed “You’re talking about no or very few valley fills that are going to meet standards like this.”

Last April, the EPA announced new guidance standards for new and pending surface mine permits in Appalachia. EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson stated “Coal communities should not have to sacrifice their environment or their health or their economic future to mountaintop mining. They deserve the full protection of our clean water laws.” The Administrator proclaimed “You’re talking about no or very few valley fills that are going to meet standards like this.”

Senator Mikulski serves on the; Appropriations Committee where she is the chairwoman of the Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies subcommittee, Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee where she is the chairwoman of the Retirement and Aging subcommittee, and the Select Committee on Intelligence.

Senator Mikulski serves on the; Appropriations Committee where she is the chairwoman of the Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies subcommittee, Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee where she is the chairwoman of the Retirement and Aging subcommittee, and the Select Committee on Intelligence. Mounting evidence shows mountaintop removal is detrimental to the

Mounting evidence shows mountaintop removal is detrimental to the

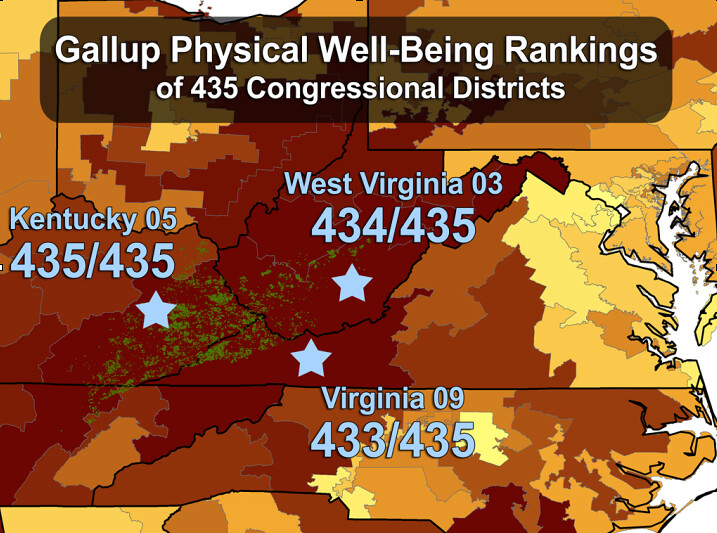

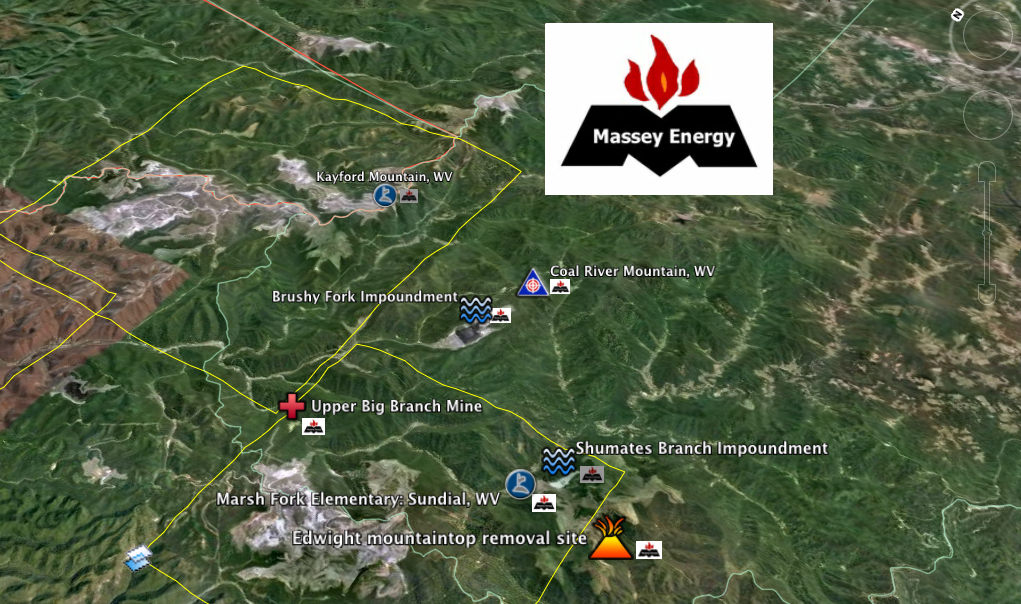

It’s been over 8 weeks since the deadly explosion at Massey Energy’s Upper Big Branch (UBB) mine claimed the lives of 29 American Miners in Raleigh County, West Virginia. The incident, which was our nation’s deadliest mining accident in 40 years, was unquestionably made more tragic by the fact that it was preventable. In order to ensure that no similar, preventable, coal-related tragedy occurs, it is critically important that we recognize the full breadth of the coal industry’s impact on Appalachian communities and ecology, while collectively accepting shared responsibility for addressing its transgressions. Step one, as they say, is admitting we have a problem.

It’s been over 8 weeks since the deadly explosion at Massey Energy’s Upper Big Branch (UBB) mine claimed the lives of 29 American Miners in Raleigh County, West Virginia. The incident, which was our nation’s deadliest mining accident in 40 years, was unquestionably made more tragic by the fact that it was preventable. In order to ensure that no similar, preventable, coal-related tragedy occurs, it is critically important that we recognize the full breadth of the coal industry’s impact on Appalachian communities and ecology, while collectively accepting shared responsibility for addressing its transgressions. Step one, as they say, is admitting we have a problem. Let’s take a closer look at Massey Energy, the company (

Let’s take a closer look at Massey Energy, the company (

Massey Energy CEO Don Blankenship remained cool and unapologetic over his company’s role in the Upper Big Branch disaster during last week’s Senate hearing on mine safety. Legislators in the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services grilled Blankenship over his company’s safety record, as they attempted to determine what must be done to improve mine safety and enforcement following the worst mining accident in 40 years.

Massey Energy CEO Don Blankenship remained cool and unapologetic over his company’s role in the Upper Big Branch disaster during last week’s Senate hearing on mine safety. Legislators in the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services grilled Blankenship over his company’s safety record, as they attempted to determine what must be done to improve mine safety and enforcement following the worst mining accident in 40 years.

Bipartisan support is growing around legislation that would conserve energy, save Americans money on their power bills, and create tens of thousands of domestic jobs.

Bipartisan support is growing around legislation that would conserve energy, save Americans money on their power bills, and create tens of thousands of domestic jobs.

issued their long awaited proposal for new rules on how to regulate the disposal and storage of coal combustion waste (CCW), the byproduct of coal-fired power plants.

issued their long awaited proposal for new rules on how to regulate the disposal and storage of coal combustion waste (CCW), the byproduct of coal-fired power plants.